Your vision will become clear only when you look into your heart.... Who looks outside, dreams. Who looks inside, awakens. Carl Jung

Monday, May 27, 2024

Why Caravaggio was as shocking as his paintings

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20161010-why-caravaggio-was-a-shocking-as-his-paintings

Why Caravaggio was as shocking as his paintings

11 October 2016

By Alastair Sooke,Features correspondent

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/images/ic/1024xn/p04blqx2.jpg.webp

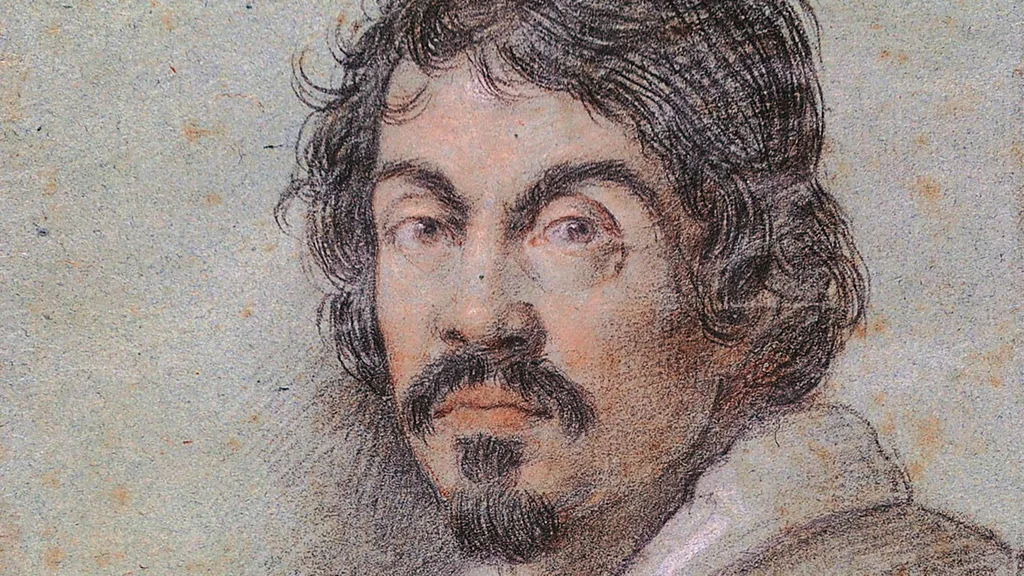

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio/Wikipedia

Caravaggio’s revolutionary style influenced everyone from modern photographers to Scorsese – but his life was just as provocative as his paintings, writes Alastair Sooke.

Is any artist’s biography more compelling than the life of the Italian painter Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610)? He has a reputation, of course, as the rebellious, hot-tempered punk of art history, pitching up in Rome in the final decade of the 16th Century, and electrifying the art world as much for his quarrelsome antics as his unconventional pictures.

According to one early biographer, the Flemish writer Karel van Mander, Caravaggio used to work intensively for a fortnight and then “swagger about for a month or two with a sword at his side … from one tennis-court to the next, ever ready to engage in a fight or an argument, with the result that it is most difficult to get along with him”.

In the early years of the 17th Century, he was brought to trial on at least 11 occasions

Not half: in the early years of the 17th Century, he was brought to trial on at least 11 occasions. The charges included swearing at a constable, penning satirical verses about a rival painter, and chucking a plate of artichokes in a waiter’s face.

And then, in 1606, he was forced to flee Rome, after killing a man during a brawl sparked by a dispute over a game of tennis. He spent the rest of his life on the run, before he collapsed and died, in the summer of 1610, while travelling back to Rome to seek a pardon from the pope.

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/images/ic/1024xn/p04blr6p.jpg.webp

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio/Wikipedia

The Calling of St Matthew is one of two large canvasses that turned Caravaggio into a star overnight (Credit: Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio/Wikipedia)

As for his paintings, well, they were just as provocative as the man who created them. According to Letizia Treves, the curator of Beyond Caravaggio, a new exhibition at the National Gallery in London exploring the dramatic influence of the Italian painter upon 17th-Century art, Caravaggio revolutionised art history in several ways.

First, he used models in an unorthodox and novel manner – pulling into his studio people from the streets whom he then painted directly from life. “Artists had always drawn from life,” Treves explains, “but no one posed their models and painted directly from life onto their final canvas. Caravaggio didn’t bother with the academic study of drawing. He skipped that stage because he believed in the importance of looking at nature.” This resulted in paintings remarkable for their striking, in-your-face realism, which captured even the humblest details: if the model had dirty fingernails, for instance, then Caravaggio would paint them.

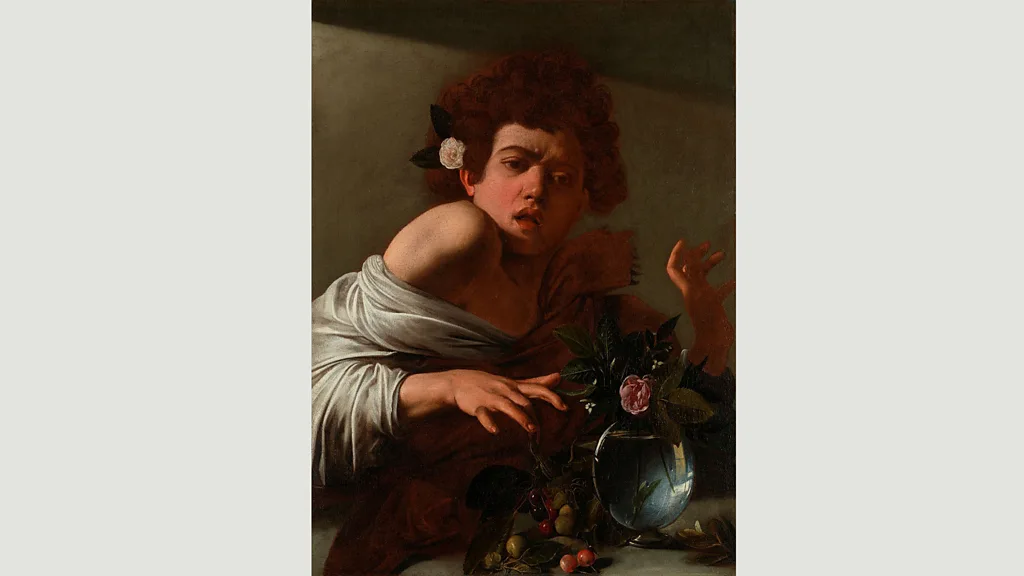

The National Gallery, London

A rose and sprig of jasmine inside a glass vase beside some cherries are placed prominently in the foreground in Boy Bitten by a Lizard (Credit: The National Gallery, London)

A corollary of this was that Caravaggio lavished as much attention on inanimate objects as he did on people: look, for instance, at the magnificent still life – a rose and sprig of jasmine inside a glass vase, beside some cherries – placed prominently in the foreground Boy Bitten by a Lizard from the National Gallery’s own collection. “He really elevated still life, which was the lowest genre,” Treves continues. “He is said to have remarked that painting still life requires as much artistry as painting figures. That was really revolutionary.”

Light and shade

Caravaggio’s second big innovation, meanwhile, was his use of light. “That’s what he’s most famous for,” says Treves. “It’s what the biographers talk about – that he wouldn’t allow anyone to pose in daylight, that he had light shine from above. He used light to capture form, create space, and add drama to otherwise everyday scenes.”

The Supper at Emmaus, also in the National Gallery, is a case in point. At supper one evening shortly after the crucifixion, two of Jesus’s disciples suddenly realise that their dinner companion is in fact the resurrected Christ. “It’s a moment of revelation, and the light underpins that narrative,” Treves says. “So Caravaggio uses light in an emblematic way, not just as theatre. It’s very sophisticated.”

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/images/ic/1024xn/p04bls8k.jpg.webp

The National Gallery, London

The Supper at Emmaus shows how Caravaggio used light to capture form and add drama (Credit: The National Gallery, London)

This combination of realism and dramatic lighting resulted in exceptionally powerful storytelling. “Caravaggio made these Biblical stories so vivid,” Treves says. “He brought them into his own time – and he involves you, so that you don’t just passively watch. Even today, you don’t need to know the story of The Supper at Emmaus in order to feel involved in the drama.”

John Ruskin castigated Caravaggio for his ‘vulgarity’, ‘dullness’, and ‘impiety’

Beyond Caravaggio explores the impact of the Italian’s art upon his contemporaries and followers. ‘Caravaggio mania’ raged across Europe in the early decades of the 17th Century, as wealthy patrons competed to buy his pictures, and artists emulated, or simply ripped off, his distinctive style. The National Gallery’s exhibition offers a chance to consider the varying talents of these artists, including the Dutchmen Dirck van Baburen and Gerrit van Honthorst, as well as the French painter Valentin de Boulogne, who are often grouped together as ‘Caravaggists’.

The curious thing is that by the middle of the 17th Century, the vogue for painting in the manner of Caravaggio had passed. “There was a real shift in taste back to classicism,” explains Treves. “And the naturalistic way of painting that Caravaggio had introduced was seen as the antithesis of that noble tradition of painting going back to Raphael.”

It would take almost three centuries before Caravaggio’s reputation rose again. To give you a sense of how low his stock tumbled, consider The Supper at Emmaus: the only reason that it ended up in the National Gallery in 1839 was because its owner had failed to sell the painting at auction eight years earlier. The important 19th-Century British art critic John Ruskin castigated Caravaggio for his “vulgarity”, “dullness”, and “impiety”, and lamented the fact that the Italian had supposedly overlooked beauty in favour of “horror and ugliness, and filthiness of sin”. Ouch.

‘Hookers and hustlers’

Things changed, though, during the 20th Century, when Caravaggio came back into fashion – largely as a result of a ground-breaking monographic exhibition staged by the art historian Roberto Longhi in Milan in 1951. Following his return to prominence, Caravaggio once more began to inspire artists in various fields.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, his use of light had a big influence upon film-makers and photographers. The photographer David LaChapelle, for instance, has spoken about the “really big impact” that Derek Jarman’s film Caravaggio (1986) had upon him. Inspired to find out more about him, LaChapelle discovered that Caravaggio had painted “the courtesans and the street people, the hookers and the hustlers”. This in turn informed his own photographic series Jesus Is My Homeboy, which featured people from the street dressed in modern clothing.

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/images/ic/1024xn/p04blrfz.jpg.webp

Cinevista

Derek Jarman’s film Caravaggio (1986) featured Dexter Fletcher as the young artist – David LaChapelle has sited it as an influence (Credit: Cinevista)

Even the film director Martin Scorsese admires Caravaggio. Quoted in Andrew Graham-Dixon’s Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane, Scorsese says: “I was instantly taken by the power of [Caravaggio’s] pictures … You come upon the scene midway and you’re immersed in it … It was like modern staging in film: it was so powerful and direct. He would have been a great filmmaker, there’s no doubt about it.”

According to Scorsese, the bar sequences in Mean Streets (1973) were a direct homage to Caravaggio: “It’s basically people sitting in bars, people at tables, people getting up. The Calling of St Matthew [one of two large canvases that Caravaggio painted for the Contarelli Chapel in the church of San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome, which turned him into a star almost overnight], but in New York! Making films with street people was what it was really about, like he made paintings with them.”

He would have been a great filmmaker, there’s no doubt about it – Martin Scorcese

Visual artists, too, are once again making work directly inspired by Caravaggio. Two years ago, the British artist Mat Collishaw staged Black Mirror, an exhibition at the Galleria Borghese in Rome that responded to its exquisite collection. Three of the works consisted of highly ornate black picture frames surrounding dark mirrors reflecting back the surrounding galleries. Within each mirror it was possible to make out a flickering simulacrum of a famous painting by Caravaggio in the Galleria Borghese.

Alamy

According to Scorsese, the bar scenes in Mean Streets are a direct homage to Caravaggio (Credit: Alamy)

“I wanted to go back to the moment when Caravaggio was immortalising the humble models in front of him – turning them from living, breathing human beings into icons of Western painting,” Collishaw explains. “Appearing from behind the mirror is this shimmering image of a man or a woman holding a slightly jittery pose, a chimerical spirit-presence coming back to haunt you through the mirror.”

This spectral effect imbued Collishaw’s black mirrors with a kind of sinister sorcery. They looked like they should be hanging in a necromancer’s hideaway rather than a gallery. According to Collishaw, the dark backgrounds of Caravaggio’s paintings allowed him to achieve the subtle effects he had in mind. Yet Collishaw also says that Caravaggio has inspired him throughout his life. He passionately believes that Caravaggio still matters in the 21st Century.

“He’s one of those artists you don’t need to read about and study because, as a painter, he’s so visceral: he just hits you right there,” he explains. “When Caravaggio was painting, the common people weren’t going to church looking for lessons in aesthetics and art history. They just wanted a relationship with God. And Caravaggio gave it to them in a language they could understand. He’s so brutally real. He doesn’t embellish or decorate things, but gives you life as it is – with dirty feet right in your face.”

Today, Collishaw says, Caravaggio’s tempestuous character is almost as important – as the template for the volatile, anti-bourgeois artist – as his art. “It’s not just what he painted but who he was,” he explains. “He was a man of the night. He used to wander around in the shadows with his cutlass hanging from him, drinking and fighting alongside prostitutes and petty criminals. I think of Francis Bacon stalking Soho at night in the ‘50s.” Collishaw pauses. “Who isn’t influenced by Caravaggio? The immediacy of his paintings is something that I and a lot of other artists have responded to. They just seem so contemporary.”

Alastair Sooke is Art Critic and Columnist for The Daily Telegraph

Related Links:

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-56675290

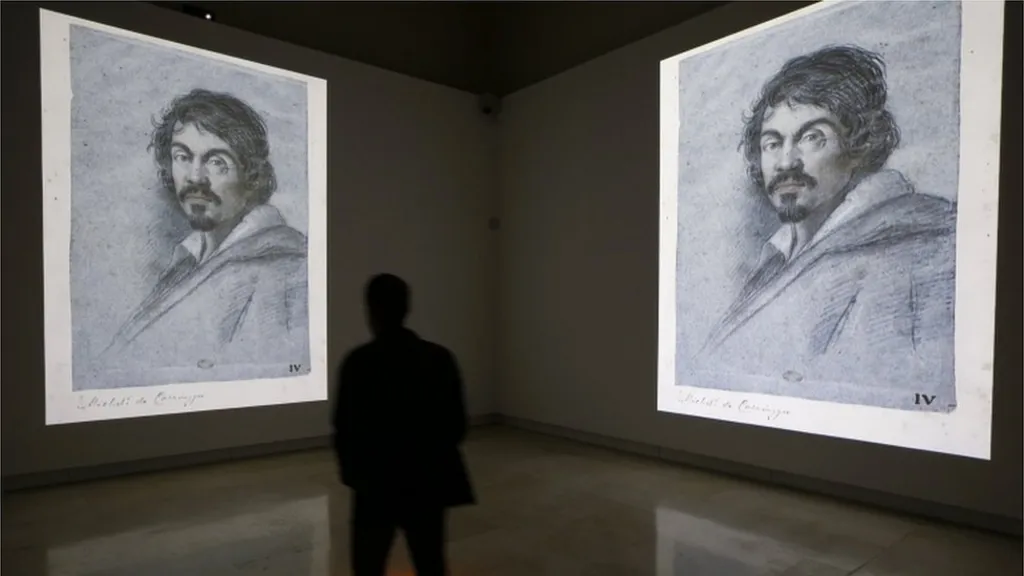

• Caravaggio - whose real name was Michelangelo Merisi - was born in 1571 or 1573 and had a violent and chaotic life, dying in mysterious circumstances at the age of 38.

• He pioneered the Baroque painting technique known as chiaroscuro, in which light and shadow are sharply contrasted.

• He was famed for starting brawls, often ended up in jail, and even killed a man.

• He was allegedly on his way to Rome to seek a pardon when he died, having spent the last few years of his life fleeing justice in southern Italy.

More:

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-oxfordshire-50131570

The art of hunting down stolen treasures

15 November 2019

By Michael Race,BBC News