Your vision will become clear only when you look into your heart.... Who looks outside, dreams. Who looks inside, awakens. Carl Jung

Monday, May 27, 2024

Carebot

Carebot

Trần Mộng Tú

Bà Hishako ngồi trong một chiếc ghế khá to, chung quanh thân hình mỏng manh, bé tí, của bà bao nhiêu là gối, chăn, chèn, chắn để những cái xương của bà được bọc êm ái không chạm vào thành ghế cứng. Bà nhìn qua khung cửa kính, mảnh vườn nhỏ cuối thu ngoài kia đã bắt đầu trống trải, xơ xác, lá rụng hết rồi. Những cái cành khẳng khiu vươn ra như những cánh tay gầy không mặc áo, chúng đang chờ mùa đông tới.

Ông Kentaro chồng bà, ngồi trên một chiếc xe lăn, không xa bà mấy. Tóc ông rụng gần hết, mấy sợi còn lại trắng như cước dính sát vào da đầu. Cái kính ông đeo trễ xuống chỏm mũi, ông cũng chẳng cần sửa lại. Ngoài kia có cái gì đáng ngắm đâu.

“Mùa thu đã hết” - ông lẩm bẩm trong miệng. Bà không nghe thấy, mà thật ra bà cũng chẳng để ý, ông nói đến lần thứ ba, bà mới nghe rõ, bà chỉ gật đầu đáp lại.

Mùa thu đã hết, mùa phơi hồng cũng chấm đứt. Bà mơ màng nhớ lại thời trẻ của hai ông bà. Chao ôi sao mà đẹp thế. Ông bà có vất vả thật. Hết làm ruộng đến trồng rau, qua làm rau thì đến đợt phơi hồng. Làm ruộng thì nhà cũng chỉ có ba sào, trồng rau thì khoảng ba mươi chiếu (*), hồng thì nhà có năm cây cổ thụ, mỗi cây cho từ hai trăm tới ba trăm trái. Ông bà có việc làm quanh năm, nhờ thế mới có tiền cho ba đứa con ăn học. Bà nhớ hồi nhỏ các con cũng phụ với ông bà xếp những trái hồng đã phơi khô vào thùng để bỏ mối. Nói đến hồng bà lại nhớ hình ảnh ông lúc còn khỏe, còn trẻ, một ngày ông hái cả ngàn quả hồng và ông luôn luôn nhớ không bao giờ hái hết, phải chừa lại một ít quả trên cây như một niềm tin cần thiết cho mùa thu hoạch năm tới được tốt đẹp, (người Nhật gọi là Kimorigaki) và để cho những chú chim ruồi mejiro có thức ăn trong mùa đông nữa. Bà nhớ là khi hai vợ chồng làm ruộng hay trồng rau, luôn luôn phải để dành một luống không gặt hết lúa, không cắt hết rau cho những con chim, con chuột đồng, con sâu, cái kiến được no lòng. Ngay cả những thân cây khô, những đống củi cũng là nơi trú ẩn cho những sinh vật nhỏ bé như con ong, con sâu, ông bà cũng không bao giờ nỡ đuổi chúng đi.

Cái văn hóa tốt đẹp này của người Nhật được cả thế giới ngưỡng mộ.

Bây giờ ông 88 tuổi rồi, bà kém ông 3 tuổi. Cả hai cùng mong manh yếu đuối. Kết quả của mấy chục năm làm việc đồng áng trong nắng, trong tuyết, bốn bàn tay gầy guộc co quắp lại. Cả hai ông bà không còn cầm được cái gì cho vững chắc trên tay nữa, di chuyển cũng trên cái ghế có bánh xe.

Ba người con lên tỉnh học, lập gia đình rồi ở lại. Họ không thể về quê sống, vì không có công việc thích hợp với những chuyên môn kiến thức của họ. Họ cũng không mang ông bà đi được vì nhà cửa ở tỉnh chật hẹp và đắt đỏ. Ông bà vẫn sống trong căn nhà của sáu mươi năm về trước, ngôi nhà từ hồi ông bà lấy nhau. Các con có sắm sửa một ít đồ đạc cho tiện nghi đời sống như tủ lạnh và máy giặt, bếp điện. Đấy là từ mười năm về trước khi ông bà còn tự chăm sóc cho mình được. Bây giờ thì phải có người để dùng những đồ đạc tiện nghi và văn minh đó.

Con cái những ngày lễ, ngày nghỉ phép thay nhau thỉnh thoảng về thăm, ở một vài ngày rồi đi. Mấy đứa cháu chơi với ông bà vài ngày cũng chán vì nhà và vườn không còn gì hấp dẫn khi không có người săn sóc và ông bà càng ngày càng chậm, đi không vững, nghe không rõ. Ba người con cùng thương cha mẹ nhưng họ không biết làm gì khác hơn. Họ cũng có thuê người mang thức ăn tới, nhưng lại không đủ tiền mướn một người làm tất cả các việc lặt vặt và ở luôn trong nhà. Cuối cùng họ chung nhau tiền mua cho ông bà một anh carebot.

Anh carebot này rất giỏi, anh làm gần như đủ mọi việc, anh có thể bế ông bà từ ghế vào giường, từ giường vào nhà tắm. Anh biết sửa soạn bữa ăn cho ông bà, miễn là trong tủ lạnh hay trên kệ có sẵn thức ăn đã nấu hay đồ hộp.

Bà Hishako và ông Kentaro mới đầu buồn tủi lắm, khi thấy mình được (hay bị) săn sóc bằng người máy, nhưng dần dần họ phải miễn cưỡng chấp nhận thôi. Ngoài thức ăn một tuần hai lần có người giao tới nhà, bỏ tủ lạnh cho. Tất cả các công việc khác từ hâm nóng thức ăn, bế vào giường, làm vệ sinh nhà cửa, giúp giặt giũ, tắm rửa hoàn toàn trông vào carebot.

Từ ngày có carebot con cháu của ông bà hình như đến thăm ít hơn. Bà nghĩ chúng bận làm, bận học. Nhưng ông thì không nghĩ thế, ông nói :

- Chúng nó giao bà với tôi cho người máy rồi.

Bà an ủi ông : - Nhưng ông không thấy người máy cũng biết ôm ấp à. Thỉnh thoảng Sato (tên ông bà đặt cho carebot) chẳng ôm tôi là gì.

Cứ như vậy đã ba, bốn mùa hồng đi qua, hình ảnh con cháu mờ dần trong hai cặp mắt già nua. Những mảnh đất lâu năm không ai trồng trọt, tự nó đã mọc đầy cỏ dại, những cây hồng không ai hái, trái rụng, chết mục khắp mặt đất. Hai ông bà như hai con chim già trong một cái lồng bắt đầu xiêu đổ.

Ông Kentaro ra hiệu cho Sato đến đùn chiếc ghế lại gần vợ. Ông đưa bàn tay khẳng khiu của mình sang nắm bàn tay khô mốc của vợ; bà biết ông sắp muốn nói điều gì, bà nghiêng đầu dựa sát vào vai ông để nghe cho rõ.

Ông nói vào tai vợ : - Tại sao văn hóa của người Nhật đối với thiên nhiên tốt đẹp như thế !

Họ chia mùa màng cho chim chóc, muông thú, sự quan tâm tối đa. Sao họ lại để cho những mảnh kim loại, những thiết bị điện tử săn sóc cha mẹ họ. Khi các con còn nhỏ tôi với bà thay nhau bế ẵm, thay nhau cho con bú mớm. Con khỏe mạnh mình cười, con ốm đau mình khóc. Mình có giao cho ai đâu, thậm chí con chó, con mèo chơi với con cũng phải ngay bên cạnh mình. Bây giờ tôi với bà có chết trong nhà này thì anh Sato chắc là chạy chung quanh mình kêu bíp bíp… Anh ta sẽ kêu hoài như thế cho tới khi chị Junko mang thức ăn tới, có thể là ba hay bốn ngày hôm sau.

Bà im lặng nghe ông nói, không biết trả lời thế nào. Bà nhớ khi anh con trai trưởng mang Sato tới cho ông bà, anh có nói :

- Cha mẹ đừng lo sợ gì, có carebot là như có con ở bên cạnh, anh ta làm hết được mọi việc, có khi còn giỏi hơn con nữa. Mà cha mẹ có biết không, bây giờ thanh niên Nhật họ lười cưới “vợ người” lắm, họ chỉ cần mua một cô vợ robot về là được đủ việc và chỉ tốn tiền có một lần thôi. Họ sẽ không cần phải làm việc nhiều để nuôi gia đình như con bây giờ đâu.

Bà nhớ là bà đã hốt hoảng nhìn xem cô con dâu có đứng gần đó không ? Cô đó nhạy cảm lắm, nghe được thì gia đình sẽ mất vui. May quá, cô ấy đang chuyện trò gì đó với hai đứa con.

Khi con cháu ra về hết để lại anh Sato, ông bà cũng mất cả tuần lễ mới quen với cách đi đứng, cách chăm sóc của anh. Bây giờ dù muốn hay không ông bà cũng phải chấp nhận sự hiện diện của anh. Không như chồng, lúc nào cũng than phiền là anh ta bằng máy, những va chạm của anh cứng ngắc, anh ta không có cảm xúc khi chăm sóc mình.

Bà Hisako mỗi lần nhận được điều gì của anh, bà cố hình dung ra anh là người bằng xương bằng thịt. Thậm chí khi anh bế bà từ ghế vào giường bà nghe được cả hơi thở và nhịp tim anh đập. Bà có tưởng tượng thái quá không ?

Chị Junko mang thức ăn nấu sẵn tới như thường lệ, chị cất thức ăn vào tủ lạnh rồi đi tìm Sato. Chị cũng có bổn phận kiểm soát lại Sato mỗi khi chị đến, xem chức năng phục vụ của anh có cần điều chỉnh lại không ?

Căn nhà im ắng quá, thật ra cả ba người này có bao giờ gây tiếng động to nào đâu. Chị đi từ nhà ngoài vào tận buồng ngủ của ông bà mới gặp cả ba người.

Trên hai chiếc giường nhỏ kê song song cạnh nhau. Bà Hisako và ông Kentaro nằm như ngủ, nằm rất thẳng thắn trên gối và chăn đáp ngang ngực. Sato đứng gập người, như cúi lạy dưới chân giường của hai người. Chị đến gần, áp mặt mình vào mặt bà, rồi lại áp sang mặt ông. Cả hai đều không còn thở nữa. Chị chạm tay mình lên vai Sato, anh ta không có phản ứng nào, không phát ra tiếng động nào, hình như anh cũng đã “chết”.

Junko lặng lẽ đi ra khỏi nhà, khép rất nhẹ cánh cửa lại sau lưng mình. Hành động của chị như một người máy.

Trần Mộng Tú

Why Caravaggio was as shocking as his paintings

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20161010-why-caravaggio-was-a-shocking-as-his-paintings

Why Caravaggio was as shocking as his paintings

11 October 2016

By Alastair Sooke,Features correspondent

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/images/ic/1024xn/p04blqx2.jpg.webp

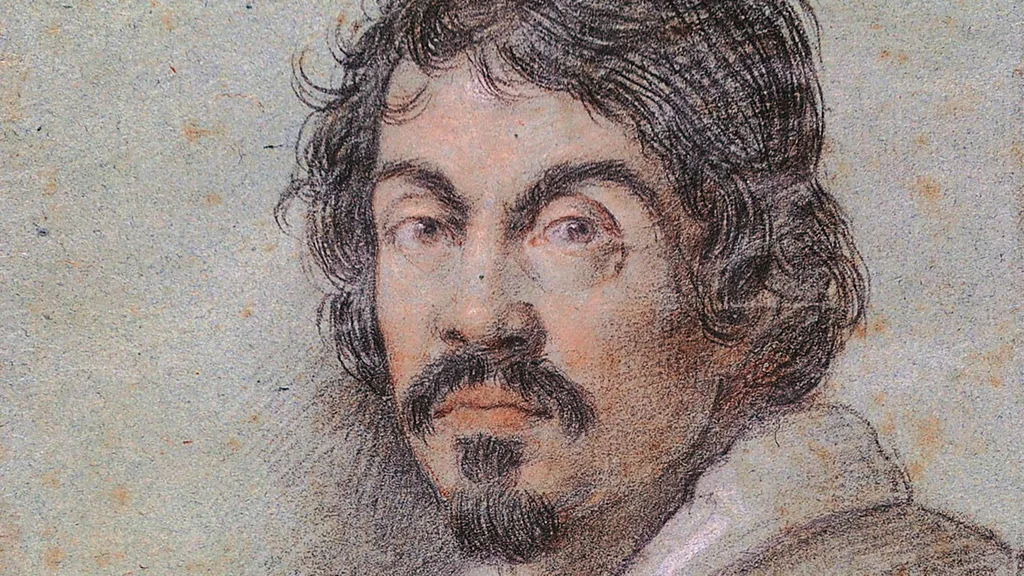

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio/Wikipedia

Caravaggio’s revolutionary style influenced everyone from modern photographers to Scorsese – but his life was just as provocative as his paintings, writes Alastair Sooke.

Is any artist’s biography more compelling than the life of the Italian painter Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610)? He has a reputation, of course, as the rebellious, hot-tempered punk of art history, pitching up in Rome in the final decade of the 16th Century, and electrifying the art world as much for his quarrelsome antics as his unconventional pictures.

According to one early biographer, the Flemish writer Karel van Mander, Caravaggio used to work intensively for a fortnight and then “swagger about for a month or two with a sword at his side … from one tennis-court to the next, ever ready to engage in a fight or an argument, with the result that it is most difficult to get along with him”.

In the early years of the 17th Century, he was brought to trial on at least 11 occasions

Not half: in the early years of the 17th Century, he was brought to trial on at least 11 occasions. The charges included swearing at a constable, penning satirical verses about a rival painter, and chucking a plate of artichokes in a waiter’s face.

And then, in 1606, he was forced to flee Rome, after killing a man during a brawl sparked by a dispute over a game of tennis. He spent the rest of his life on the run, before he collapsed and died, in the summer of 1610, while travelling back to Rome to seek a pardon from the pope.

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/images/ic/1024xn/p04blr6p.jpg.webp

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio/Wikipedia

The Calling of St Matthew is one of two large canvasses that turned Caravaggio into a star overnight (Credit: Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio/Wikipedia)

As for his paintings, well, they were just as provocative as the man who created them. According to Letizia Treves, the curator of Beyond Caravaggio, a new exhibition at the National Gallery in London exploring the dramatic influence of the Italian painter upon 17th-Century art, Caravaggio revolutionised art history in several ways.

First, he used models in an unorthodox and novel manner – pulling into his studio people from the streets whom he then painted directly from life. “Artists had always drawn from life,” Treves explains, “but no one posed their models and painted directly from life onto their final canvas. Caravaggio didn’t bother with the academic study of drawing. He skipped that stage because he believed in the importance of looking at nature.” This resulted in paintings remarkable for their striking, in-your-face realism, which captured even the humblest details: if the model had dirty fingernails, for instance, then Caravaggio would paint them.

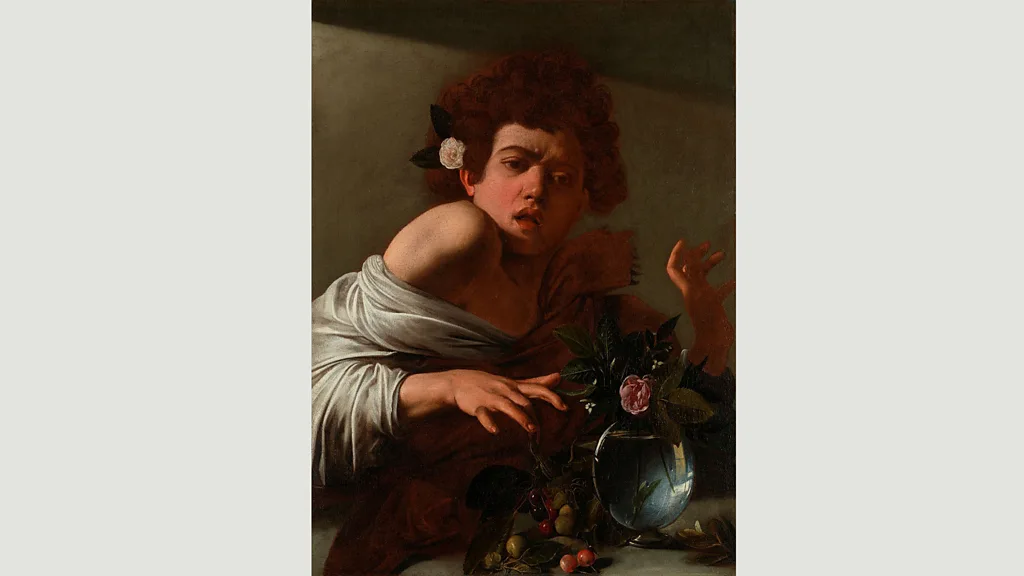

The National Gallery, London

A rose and sprig of jasmine inside a glass vase beside some cherries are placed prominently in the foreground in Boy Bitten by a Lizard (Credit: The National Gallery, London)

A corollary of this was that Caravaggio lavished as much attention on inanimate objects as he did on people: look, for instance, at the magnificent still life – a rose and sprig of jasmine inside a glass vase, beside some cherries – placed prominently in the foreground Boy Bitten by a Lizard from the National Gallery’s own collection. “He really elevated still life, which was the lowest genre,” Treves continues. “He is said to have remarked that painting still life requires as much artistry as painting figures. That was really revolutionary.”

Light and shade

Caravaggio’s second big innovation, meanwhile, was his use of light. “That’s what he’s most famous for,” says Treves. “It’s what the biographers talk about – that he wouldn’t allow anyone to pose in daylight, that he had light shine from above. He used light to capture form, create space, and add drama to otherwise everyday scenes.”

The Supper at Emmaus, also in the National Gallery, is a case in point. At supper one evening shortly after the crucifixion, two of Jesus’s disciples suddenly realise that their dinner companion is in fact the resurrected Christ. “It’s a moment of revelation, and the light underpins that narrative,” Treves says. “So Caravaggio uses light in an emblematic way, not just as theatre. It’s very sophisticated.”

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/images/ic/1024xn/p04bls8k.jpg.webp

The National Gallery, London

The Supper at Emmaus shows how Caravaggio used light to capture form and add drama (Credit: The National Gallery, London)

This combination of realism and dramatic lighting resulted in exceptionally powerful storytelling. “Caravaggio made these Biblical stories so vivid,” Treves says. “He brought them into his own time – and he involves you, so that you don’t just passively watch. Even today, you don’t need to know the story of The Supper at Emmaus in order to feel involved in the drama.”

John Ruskin castigated Caravaggio for his ‘vulgarity’, ‘dullness’, and ‘impiety’

Beyond Caravaggio explores the impact of the Italian’s art upon his contemporaries and followers. ‘Caravaggio mania’ raged across Europe in the early decades of the 17th Century, as wealthy patrons competed to buy his pictures, and artists emulated, or simply ripped off, his distinctive style. The National Gallery’s exhibition offers a chance to consider the varying talents of these artists, including the Dutchmen Dirck van Baburen and Gerrit van Honthorst, as well as the French painter Valentin de Boulogne, who are often grouped together as ‘Caravaggists’.

The curious thing is that by the middle of the 17th Century, the vogue for painting in the manner of Caravaggio had passed. “There was a real shift in taste back to classicism,” explains Treves. “And the naturalistic way of painting that Caravaggio had introduced was seen as the antithesis of that noble tradition of painting going back to Raphael.”

It would take almost three centuries before Caravaggio’s reputation rose again. To give you a sense of how low his stock tumbled, consider The Supper at Emmaus: the only reason that it ended up in the National Gallery in 1839 was because its owner had failed to sell the painting at auction eight years earlier. The important 19th-Century British art critic John Ruskin castigated Caravaggio for his “vulgarity”, “dullness”, and “impiety”, and lamented the fact that the Italian had supposedly overlooked beauty in favour of “horror and ugliness, and filthiness of sin”. Ouch.

‘Hookers and hustlers’

Things changed, though, during the 20th Century, when Caravaggio came back into fashion – largely as a result of a ground-breaking monographic exhibition staged by the art historian Roberto Longhi in Milan in 1951. Following his return to prominence, Caravaggio once more began to inspire artists in various fields.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, his use of light had a big influence upon film-makers and photographers. The photographer David LaChapelle, for instance, has spoken about the “really big impact” that Derek Jarman’s film Caravaggio (1986) had upon him. Inspired to find out more about him, LaChapelle discovered that Caravaggio had painted “the courtesans and the street people, the hookers and the hustlers”. This in turn informed his own photographic series Jesus Is My Homeboy, which featured people from the street dressed in modern clothing.

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/images/ic/1024xn/p04blrfz.jpg.webp

Cinevista

Derek Jarman’s film Caravaggio (1986) featured Dexter Fletcher as the young artist – David LaChapelle has sited it as an influence (Credit: Cinevista)

Even the film director Martin Scorsese admires Caravaggio. Quoted in Andrew Graham-Dixon’s Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane, Scorsese says: “I was instantly taken by the power of [Caravaggio’s] pictures … You come upon the scene midway and you’re immersed in it … It was like modern staging in film: it was so powerful and direct. He would have been a great filmmaker, there’s no doubt about it.”

According to Scorsese, the bar sequences in Mean Streets (1973) were a direct homage to Caravaggio: “It’s basically people sitting in bars, people at tables, people getting up. The Calling of St Matthew [one of two large canvases that Caravaggio painted for the Contarelli Chapel in the church of San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome, which turned him into a star almost overnight], but in New York! Making films with street people was what it was really about, like he made paintings with them.”

He would have been a great filmmaker, there’s no doubt about it – Martin Scorcese

Visual artists, too, are once again making work directly inspired by Caravaggio. Two years ago, the British artist Mat Collishaw staged Black Mirror, an exhibition at the Galleria Borghese in Rome that responded to its exquisite collection. Three of the works consisted of highly ornate black picture frames surrounding dark mirrors reflecting back the surrounding galleries. Within each mirror it was possible to make out a flickering simulacrum of a famous painting by Caravaggio in the Galleria Borghese.

Alamy

According to Scorsese, the bar scenes in Mean Streets are a direct homage to Caravaggio (Credit: Alamy)

“I wanted to go back to the moment when Caravaggio was immortalising the humble models in front of him – turning them from living, breathing human beings into icons of Western painting,” Collishaw explains. “Appearing from behind the mirror is this shimmering image of a man or a woman holding a slightly jittery pose, a chimerical spirit-presence coming back to haunt you through the mirror.”

This spectral effect imbued Collishaw’s black mirrors with a kind of sinister sorcery. They looked like they should be hanging in a necromancer’s hideaway rather than a gallery. According to Collishaw, the dark backgrounds of Caravaggio’s paintings allowed him to achieve the subtle effects he had in mind. Yet Collishaw also says that Caravaggio has inspired him throughout his life. He passionately believes that Caravaggio still matters in the 21st Century.

“He’s one of those artists you don’t need to read about and study because, as a painter, he’s so visceral: he just hits you right there,” he explains. “When Caravaggio was painting, the common people weren’t going to church looking for lessons in aesthetics and art history. They just wanted a relationship with God. And Caravaggio gave it to them in a language they could understand. He’s so brutally real. He doesn’t embellish or decorate things, but gives you life as it is – with dirty feet right in your face.”

Today, Collishaw says, Caravaggio’s tempestuous character is almost as important – as the template for the volatile, anti-bourgeois artist – as his art. “It’s not just what he painted but who he was,” he explains. “He was a man of the night. He used to wander around in the shadows with his cutlass hanging from him, drinking and fighting alongside prostitutes and petty criminals. I think of Francis Bacon stalking Soho at night in the ‘50s.” Collishaw pauses. “Who isn’t influenced by Caravaggio? The immediacy of his paintings is something that I and a lot of other artists have responded to. They just seem so contemporary.”

Alastair Sooke is Art Critic and Columnist for The Daily Telegraph

Related Links:

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-56675290

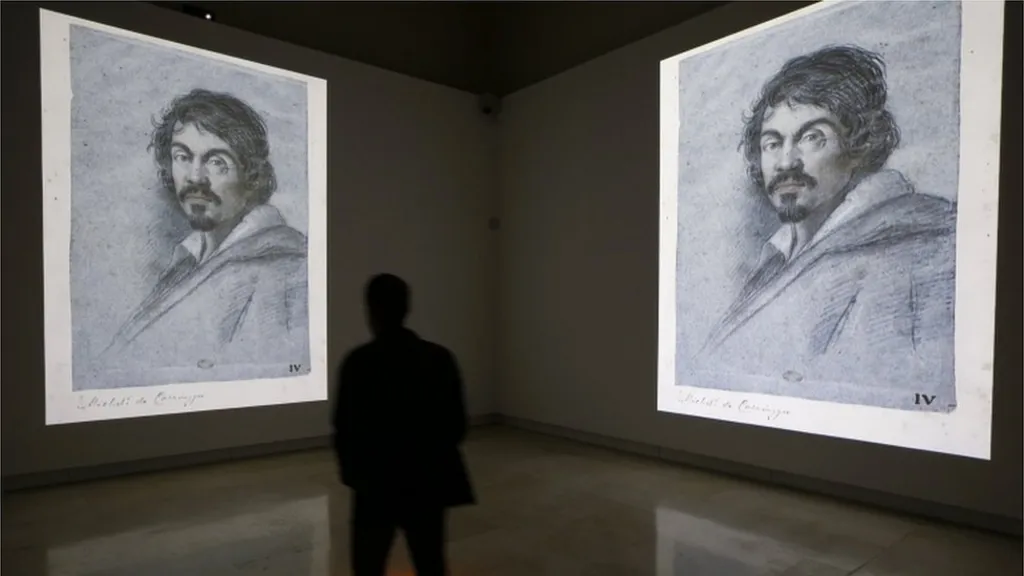

• Caravaggio - whose real name was Michelangelo Merisi - was born in 1571 or 1573 and had a violent and chaotic life, dying in mysterious circumstances at the age of 38.

• He pioneered the Baroque painting technique known as chiaroscuro, in which light and shadow are sharply contrasted.

• He was famed for starting brawls, often ended up in jail, and even killed a man.

• He was allegedly on his way to Rome to seek a pardon when he died, having spent the last few years of his life fleeing justice in southern Italy.

More:

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-oxfordshire-50131570

The art of hunting down stolen treasures

15 November 2019

By Michael Race,BBC News

Saturday, May 4, 2024

North Korean weapons are killing Ukrainians

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-68933778

North Korean weapons are killing Ukrainians. The implications are far bigger

4 hours ago

By Jean Mackenzie,Seoul correspondent

On 2 January, a young Ukrainian weapons inspector, Krystyna Kimachuk, got word that an unusual-looking missile had crashed into a building in the city of Kharkiv. She began calling her contacts in the Ukrainian military, desperate to get her hands on it. Within a week, she had the mangled debris splayed out in front of her at a secure location in the capital Kyiv.

Ms Kimachuk works for Conflict Armament Research (CAR), an organisation that retrieves weapons used in war, to work out how they were made. But it wasn't until after she had finished photographing the wreckage of the missile and her team analysed its hundreds of components, that the most jaw-dropping revelation came.

It was bursting with the latest foreign technology. Most of the electronic parts had been manufactured in the US and Europe over the past few years. There was even a US computer chip made as recently as March 2023. This meant that North Korea had illicitly procured vital weapons components, snuck them into the country, assembled the missile, and shipped it to Russia in secret, where it had then been transported to the frontline and fired - all in a matter of months.

"This was the biggest surprise, that despite being under severe sanctions for almost two decades, North Korea is still managing to get its hands on all it needs to make its weapons, and with extraordinary speed," said Damien Spleeters, the deputy director at CAR.

Photos of the Moon

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/cpsprodpb/503f/live/3a0331d0-070a-11ef-bee9-6125e244a4cd.jpg.webp

Bruce Carrington: “In this tranquil image of Druridge Bay at low tide, the wet sands shimmer in the reflected moonlight. The lights of Blyth can be seen on the horizon.”

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/cpsprodpb/1cc4/live/15dd3260-070a-11ef-b2ce-15f024debdd3.jpg.webp

Gary Peck: “Autumn on the Hunter River in New South Wales, Australia. Doing it easy, watching whatever passes by.”

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/cpsprodpb/a9d6/live/f3ba2ee0-0709-11ef-82e8-cd354766a224.jpg.webp

Dusty Danis: “I waited patiently for the moon to fall to this small gap in the trees. Once it arrived in the location where I wanted, it was time to wait for a vehicle to come down the road. Not many vehicles travel here, so I got lucky with this one.”

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/cpsprodpb/5114/live/5dedaee0-070a-11ef-82e8-cd354766a224.jpg.webp

Kevin Miller: “Peeking through a stormy night, South Jersey, USA”

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/cpsprodpb/bcb3/live/a0055cd0-070d-11ef-b2ce-15f024debdd3.jpg.webp

Hannah Hinton: “I took this photo in Manang on the Annapurna Circuit in Nepal, the halfway point of our trek. We were up early in the freezing cold but it was so worth it for views like this.”

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)