Your vision will become clear only when you look into your heart.... Who looks outside, dreams. Who looks inside, awakens. Carl Jung

Thursday, January 26, 2023

Vicente Lusitano (c. 1520 – c. 1561)

The Life and Music of Vicente Lusitano

Streamed live on Oct 2, 2022

Join University of Michigan faculty member Garrett Schumann and UK-based choir conductor Joseph McHardy for a thrilling exploration of the life and music of Afro-Portuguese Renaissance composer Vicente Lusitano. This presentation will feature video and audio of McHardy’s world-class performances of Lusitano’s compositions recorded earlier this summer, alongside discussion of the pair’s collaborative research uncovering new details of Lusitano’s music and biography. Since 2020, McHardy and Schumann’s work on Vicente Lusitano has been featured by the BBC, appeared in VAN Magazine, presented at multiple international academic conferences, and their multiple forthcoming publications on this subject include an article in the celebrated encyclopedia Grove Music Online. In June 2022, McHardy led the world’s first-ever all-Lusitano concert tour in England with an ensemble of renowned vocalists assembled in partnership with the award-winning Chineke! Foundation. Recordings from this tour will appear on a CD released through Decca in the near future. In addition to sharing their findings, Schumann and McHardy will speak to the connections between Lusitano’s misrepresentation in 500 years of classical music scholarship and this field’s historic erasure of composers of African descent and their music.

Vicente Lusitano - Inviolata | The Marian Consort

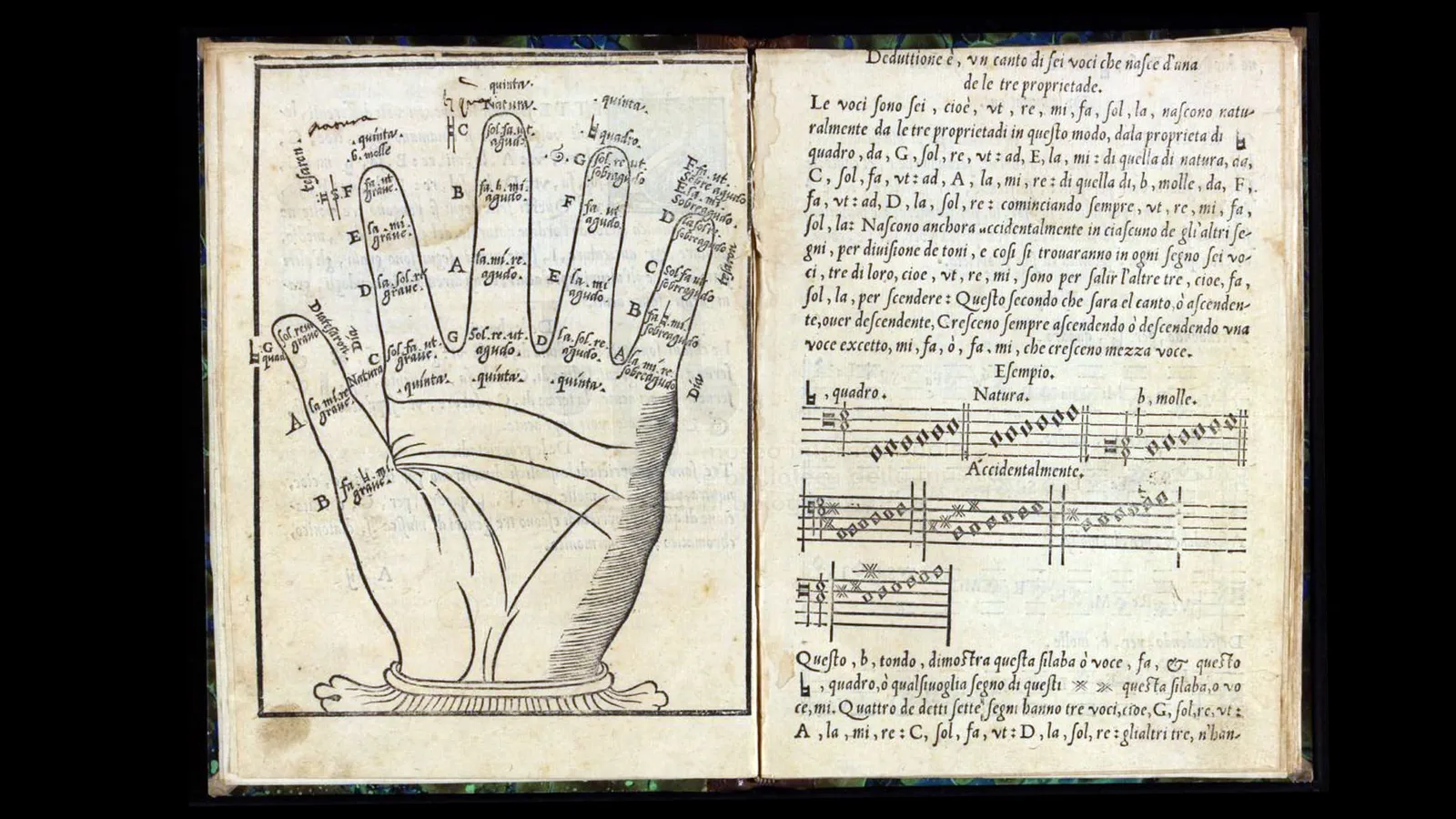

Vicente Lusitano (c. 1520 – c. 1561) was a Portuguese composer and theorist of the late Renaissance. He was possibly of African descent and has a claim to being the first published black composer. Little is known of Lusitano's life, though some information is recorded in the 18th-century biography by Diogo Barbosa Machado: he came from Olivença, became a priest, and was employed as a teacher at Padua and Viterbo. Very little of what Machado wrote about him has been verified by any other source, except the date of publication (1561) of a music theory treatise at Venice. He wrote a number of choral works, including Latin motets (published as Liber primus epigramatum que vulgo motetta dicuntur, 5, 6, 8vv, Rome, 1551).

In several works, he references Josquin des Prez, who had died 30 years before. For example, he reworked des Prez' motet Inviolata, integra for more voices. In a 1551 debate in Rome, he espoused traditional views on the role of the three genera in music (diatonic, chromatic, and enharmonic) over more radical ones put forward by Nicola Vicentino (Lusitano was deemed to have won the debate). His Introduttione facilissima, et novissima, di canto fermo, figurato, contraponto semplice, et inconcerto (Rome, 1553, and again at Venice, 1561),[6] contains an introduction to music, a section on improvised counterpoint (setting new parts above or below a cantus firmus), and his views on the three genera. Aspice Domine quia facta est was published in 1555 in Liber primus epigramatum (no. 4) and is scored for five voices. Multitrack performance here by Ben Inman.

Score: Edition found on cpdl.org.

Text and translation: Aspice, Domine, quia facta est desolata civitas plena divitiis. Sedet in tristitia, domina gentium. Non est qui consoletur eam, nisi tu, Deus noster. - Behold, O Lord, how the city full of riches is become desolate. She sits in mourning, the mistress of the nations. There is none to comfort her save only thou, our God.

The great 16th-Century black composer erased from history

(Image credit: IMSLP/Public Domain)

By Holly Williams15th June 2022

For hundreds of years, the remarkable Vicente Lusitano has been forgotten. But now, finally, both his music and his story are being heard once more, writes Holly Williams.

The Western classical music canon is notoriously white and male – so you might assume that a black Renaissance composer would be a figure of significant interest, much-performed and studied. In fact, the story of the first known published black composer – Vicente Lusitano – is only now being heard, alongside a revival of interest in his long-neglected choral music.

More like this:

– How the first pop star blazed a trail

– The singing contest that made history

– The music most embedded in our psyches

Lusitano was born around 1520, in Portugal. In a 17th-Century source, he is described as "pardo" – a commonly used term in Portugal at the time meaning mixed race. It is most likely that Lusitano had a black African mother and a white Portuguese father; Portugal had a significant population of people of African descent, due to its involvement in the slave trade.

Among other things Lusitano was an expert music theorist – this is a page from his composition manual Introduttione Facilissima (Credit: IMSLP/Public Domain)

Comparatively little is known about Lusitano's life – a fact which has certainly not helped his historical legacy – although what we do know is dotted with juicily intriguing details. "There’s a lot of things you could say about how cool he is as a person, and how exceptional he is as a figure," promises composer, conductor and early music specialist Joseph McHardy, a recent Lusitano champion.

What we do know is that Lusitano became a Catholic priest, composer, and music theorist, and in 1551 left Portugal for Rome – a multicultural musical capital of Europe at the time – most likely following a rich patron, the Portuguese ambassador. Lusitano appears to have done very well for himself there, publishing a collection of motets: sacred, polyphonic choral compositions (where voices sing several layers of independent melodies simultaneously). Then, Lusitano became embroiled in a high-profile public debate around the rules of composition and the use and juxtapositions of different tuning systems or keys, with a rival composer, Nicola Vicentino. Consider it a Twitter spat of the Renaissance age – although with an official judging panel of eminent performers from the Sistine Chapel choir, no less.

In the final adjudication of their intellectual duel, Lusitano was unanimously judged the winner: an unlikely victory given that, as a foreign outsider, he was something of an underdog compared to the well-connected Vicentino. But, unwilling to let it go, Vicentino conducted a smear campaign against Lusitano, discrediting him and his ideas. In what would become a famous, printed 1555 treatise, Vicentino fabricated a misleading version of the debate so it looked like he had the better ideas, really ¬– and it was this document that endured and this version that was later repeated in many textbooks.

Sometime after 1553, Lusitano converts to Protestantism – itself an unheard of development for an Iberian composer in the era. He also gets married, and moves to Germany; we know he receives payment for some music there in 1562, and applied for a job in Stuttgart.

But although his achievements in Rome suggests Lusitano won significant respect for his music in his lifetime, it wasn’t as widely copied or performed as some of his contemporaries, and seems not to have spread across Europe; this has led to some musicologists in Portugal appreciating him, but a failure to cut through among non-Portuguese speaking scholars since. Occasional flashes of academic interest have never transformed into sustained attention, an accessible and readily shareable modern score, or performances of the thing that really matters: his music.

The new Lusitano champions

Until, that is, very recently. During the pandemic, two Renaissance music lovers separately discovered Lusitano, and are staging concerts and bringing out records of his work, while a new piece reimagining a Lusitano composition is currently on tour across the UK.

In what he describes as the "darkest days" of the first lockdown, Rory McCleery – founder of British vocal ensemble The Marian Consort – read an article about Lusitano by an academic, Garrett Schumann from the University of Michigan, in VAN Magazine. Keen to find out more, McCleery was delighted to discover that Liber primus epigramatum, Lusitano's 1551 collection of motets, had been digitised and put online.

"My proclivities have always been in finding Renaissance composers who have fallen between the cracks," he says. "It's always super exciting when you find a composer and start looking into their music and go, actually, this is very good. You want to evangelise about it – music is there to be shared."

And share it, he did: The Marian Consort were including a Lusitano piece, Inviolata, integra et casta es, in concert programmes by December 2020 – probably the first time it had ever been performed live in the UK. Last summer, they weaved it into a Prom celebrating a much more famous Renaissance composer, Josquin des Prez. It was apt, given that Lusitano's work is clearly in dialogue with Josquin – in Inviolata, Lusitano riffed on a hugely technically accomplished five-part composition by Josquin, impressively expanding it further, for eight voices.

A woodcut of composer Josquin des Prez, with whom Lusitano's work was in dialogue; by contrast, there are no known pictures of Lusitano in existence (Credit: Alamy)

"Lusitano obviously liked to go, well this is all very clever – you've done one Rubik's Cube, now I'm going to do four Rubik's Cubes at the same time…" jokes McCleery. "But for me, what is so exciting is it’s a very beautiful piece of music, as well as a clever one."

The Marian Consort release a full album of Lusitano's music this autumn, and have also already teamed up with the organisation Classical Remix to tour a new installation, titled Lusitano Remixed, to both art galleries and music venues in the UK. Acclaimed opera singer and composer Roderick Williams was commissioned to write his own response to Lusitano's Inviolata. It plays out of eight speakers arranged in circle, one speaker for each of singer, which the listener can move around; experiencing it at the Samuel Worth Chapel in Sheffield, I found it offered an immersive, spatialised experience, soaking you in a soaring surround-sound while also allowing you to get up-close and intimate with individual voices.

Lusitano has been forgotten by history, both through malice and ignorance – Roderick Williams

"I, like most people, had never heard of Lusitano," admits Williams when discussing his piece, which directly quotes Josquin, then Lusitano, before "exploding" into his own contemporary interpretation. "The whole idea of The Marian Consort doing their research about him is that he has been forgotten by history – through malice, through ignorance. We are beginning to wake up, all of us, to the idea that there were mixed-race composers in the past."

McCleery was not the only one who had a fortuitous chance encounter with Lusitano in 2020. During Black Lives Matter protests, McHardy saw a picture on Twitter of someone holding a placard depicting black composers through history, reading 'teach these composers' – including Lusitano, who he'd never heard of. McHardy googled him, also found Schumann's article, and got in touch.

Since then, the pair have been working on the fairly mammoth task of turning Lusitano's part books – all the separate, individual vocal parts for his motets – into one unified score with modern notation, so they can be more easily understood and performed. A scholarly edition is planned, alongside a recording (likely out early next year), while there are three concerts of his work this week by black and ethnically-diverse vocal ensemble Chineke! Voices.

You might expect some rivalry, from two early music specialists, both uncovering this forgotten figure simultaneously. But both, really, just seem delighted more people might hear Lusitano's music.

"Lusitano's moment has come – he's in the zeitgeist, which is fantastic because his music really does deserve to be better known," says McCleery. And both men are also staunch in insisting that this revival of interest is not just about the eye-catching fact that Lusitano was a composer of African descent – it's that his music stands up.

The beauty of his music

"It's really difficult choosing the pieces [to include], because they’re all really good!" says McHardy, promising that Chineke!'s record, as with the concerts, will feature 90 minutes of "top level Renaissance polyphony". He also wanted to include a range of Lusitano's work: some of his "really complex eight-part masterworks" but also pieces that are significant to his story, such as his adventurously weird, chromatic motet Regina coeli, which is thought to have kicked off that feud with Vicentino.

What exactly appeals, then, about Lusitano's music? "Fundamentally, it’s just really beautiful," says McCleery. "There are very long arching phrases that seem to spin out into eternity. But also this interesting use of chromaticism: slightly spicy moments – the musical equivalent of feeling metal on metal."

If you have ever encountered Lusitano, it's likely to be his most chromatic piece, Heu me domine, which has attracted some interest since the 1980s precisely for its experimental dissonance. In fact, this etude comes from within a theoretical treatise on counterpoint and improvisation that Lusitano wrote – it was more intended to illustrate a point, than as a composition to be performed.

Composer and conductor Joseph McHardy has been one of the music experts helping to champion Lusitano (Credit: BBC)

"It’s a very cool piece. But it isn’t super representative [of Lusitano's music]," says Schumann. Instead, Schumann also reaches for the word "beautiful" when trying to summarise Lusitano’s richly layered polyphony: "It's just really, really gorgeous." "'Opulent' is a good word for it," chimes in McHardy.

The music is worth revisiting, then. But for contemporary audiences, Lusitano's identity and biography – patchy as it is – of course proves a source of enormous fascination, too.

What do we know about how his race may have affected his career prospects – in his own lifetime, and since? Much is speculation – but it is likely that Lusitano faced some prejudice, and there are specific ways his identity certainly disadvantaged him. In Portugal, he would have been barred from getting a job in one of the big, major churches because of his race. "The papal bill that allowed African descended men to be ordained Priests specifically forbad them from holding benefices in the Portuguese church," explains McHardy.

One piece that McHardy is recording, Quid Montes, Musae?, is a rare secular composition, based on a poem asking the muses to relocate to Italy with the Portuguese ambassador. McHardy speculates that Lusitano may have written the words himself – another cool and unusual thing for a composer at that time. And one that may provide a glimpse into how Lusitano felt about being pardo in Portugal…

"It talks about Portugal in some derogatory language: ravening beasts and inhospitable rocks, everything is scary and everything promises death…" explains McHardy. "On the surface, you go 'OK, this is a Renaissance person writing neo-classical stuff'. But if you put it in context – that this comes from the pen, and may well have been sung in the mouth, of someone who was discriminated against [via] Portuguese legal and societal racism – I think it has some more layers to it. It feels like his personal voice."

People have been talking with confidence that he is black for at least 50 years – and yet it is still considered controversial – Garrett Schumann

In terms of how Lusitano's race may have affected his reception since… well, that's a tale of two parts. Lusitano is described as pardo in an unpublished manuscript about Portuguese musicians by João Franco Barreto, written in the mid-1600s – but in 1752, Diogo Barbosa Machado, the author of the first printed encyclopaedia of Portuguese composers, chooses not to repeat this detail. So anyone reading about Lusitano after that would likely not have even know he had African heritage. It was only in 1977, when Portuguese musicologist Maria Augusta Alves Barbosa returned to the original unpublished manuscript, that this fact became widely known.

Was the decision not to include Lusitano's racial identity in the 18th Century itself racist? Possibly. Schumann wonders whether it may have been an act of erasure by Machado, seeking to promote a certain view of their nation through music. "At the time Portugal was being extremely legalistic about racial categories because they were trying to exclude people of African descent from property rights, so it may have been a political motivation. But it is [also] part of a broader scheme of making it seem like the only people who participated in this tradition were white men."

Vocal ensemble The Marian Consort have been performing Lusitano's music, after their founder came across a feature about him during lockdown (Credit: Lusitano Remixed)

https://ychef.files.bbci.co.uk/1600x900/p0cf3d1b.webp

Which leads us on to a point Schumann finds even more depressing: even today, he continues to meet resistance to the idea that Lusitano was black mixed-race.

"People have been talking with confidence that he is black for at least 50 years – and yet it is still considered controversial! Music scholars refuse to believe it," he says. "And the reason people find it hard to swallow is we were told there were no black composers, when there were. There is evidence that there were [unpublished] black composers in Europe in the 14th-Century. Lusitano is an important landmark – but he’s not the start of that story."

Not that it's all gloom. There seems to be an increasing appetite among the public for uncovering a more diverse musical history, and renewed efforts by people programming concerts to showcase a greater variety of work. And at least now we can put paid to the idea that there simply weren’t any non-white composers writing music in the Renaissance, McHardy points out.

"We found the music for you, here it is: it’s pretty, it sounds nice, you can read it really well… That can move things on a bit," he acknowledges. "Then people have to make a choice about whether they want to perform it or not. Which is a different situation to going 'I couldn’t find any'."

"I think the more Lusitano's music gets heard, the more people will be interested in performing it," concludes Schumann. "It's really good music."

‘Lusitano Remixed’ is at St George’s Bristol until 27 June 2022, classicalremix.org. An EP of the recording is out now, and The Marian Consort’s album, 'Vicente Lusitano: Motets' will be released 23 September.

Chineke! Voices perform ‘The Music of Vicente Lusitano’ at St George’s, Bristol on 16 June; Worcester College, Oxford on 17 June, and St Martin’s in the Fields, London on 18 June, chineke.org/events

Wednesday, January 25, 2023

Sanh Diệt và Thường Trụ

“Cái sanh diệt là thức, cái chẳng sanh diệt là trí.”

Kinh Lăng Già

Các pháp từ xưa nay

Tướng thường tự tịch diệt.

Phẩm Phương tiện, Kinh Pháp Hoa

Pháp ấy trụ vị pháp

Tướng thế gian thường trụ.

Kinh Pháp Hoa

Tuesday, January 10, 2023

The Remarkable Emptiness of Existence Tánh Không Kỳ Diệu Của Hiện Hữu

The Remarkable Emptiness of Existence

Tánh Không Kỳ Diệu Của Hiện Hữu

Early scientists didn’t know it, but we do now: The void in the universe is alive.

Các nhà khoa học trước đây không biết về điều này, nhưng nay chúng ta được biết chơn không trong vũ trụ thật sinh động.

Tác giả: Paul M. Sutter*

Dịch Việt: NT

January 4, 2023

In 1654 a German scientist and politician named Otto von Guericke was supposed to be busy being the mayor of Magdeburg. But instead he was putting on a demonstration for lords of the Holy Roman Empire. With his newfangled invention, a vacuum pump, he sucked the air out of a copper sphere constructed of two hemispheres. He then had two teams of horses, 15 in each, attempt to pull the hemispheres apart. To the astonishment of the royal onlookers, the horses couldn’t separate the hemispheres because of the overwhelming pressure of the atmosphere around them.

Vào năm 1654 nhà khoa học và chính khách Đức Otto von Guericke lẽ ra phải bận bịu với nhiệm vụ thị trưởng thành phố Magdeburg. Nhưng thay vì thế, ông lại đang lo chuyện trình bày trước các nhà lãnh đạo Thánh Đế La Mã. Với chiếc máy bơm chơn không, một phát kiến mới lạ của mình, ông hút không khí ra khỏi một quả cầu bằng đồng làm từ hai bán cầu. Rồi ông cho hai bầy ngựa, mỗi bầy 15 con, ra sức kéo để tách rời hai bán cầu ra. Trước sự kinh ngạc của các ông hoàng đang mục kích, bầy ngựa không tài nào tách hai bán cầu ra được vì áp suất không khí bao quanh hai bán cầu quá lớn.

[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holy_Roman_Empire. The Holy Roman Empire/Thánh Đế La Mã là một đế chế (một thực thể chính trị) gồm các nước trong khu vực tây, trung và nam Âu châu, phát triển vào đầu thời Trung Cổ/Dark Ages (cuối thế kỷ thứ 5, đầu thế kỷ thứ 6 kéo dài đến thế kỷ thứ 10), và giải thể vào năm 1806 trong thời kỳ chiến tranh Napoleon (1803-1815). ]

Von Guericke became obsessed by the idea of a vacuum after learning about the recent and radical idea of a heliocentric universe: a cosmos with the sun at the center and the planets whipping around it. But for this idea to work, the space between the planets had to be filled with nothing. Otherwise friction would slow the planets down.

Von Guericke bị ý tưởng về chơn không ám ảnh sau khi ông học được tư tưởng cấp tiến mới ra đời cho mặt trời là trung tâm vũ trụ và các hành tinh vận hành quanh nó. Nhưng muốn biến tư tưởng này thành hiện thực thì không gian giữa các hành tinh phải không chứa vật thể nào cả. Nếu không, sự ma sát sẽ làm các hành tinh vận hành chậm lại.

The vacuum is singing to us, a harmony underlying reality itself. Chơn không đang hát cho chúng ta nghe, một cung điệu hài hòa tiềm tàng chính nơi thực tại.Scientists, philosophers, and theologians across the globe had debated the existence of the vacuum for millennia, and here was von Guericke and a bunch of horses showing that it was real. But the idea of the vacuum remained uncomfortable, and only begrudgingly acknowledged. We might be able to artificially create a vacuum with enough cleverness here on Earth, but nature abhorred the idea. Scientists produced a compromise: The space of space was filled with a fifth element, an aether, a substance that did not have much in the way of manifest properties, but it most definitely wasn’t nothing. Trải qua hàng thiên niên kỷ, các khoa học gia, triết gia, và nhà thần học khắp thế giới đã từng tranh luận về sự hiện hữu của chơn không, thì giờ đây von Guericke và bầy ngựa lại cho thấy chơn không quả có thực. Nhưng ý tưởng về chơn không vẫn có gì đó không ổn, và người ta chỉ chấp nhận có nó một cách miễn cưỡng. Với đủ thông minh chúng ta có thể tự tạo ra một chơn không ngay trên trái đất, nhưng thiên nhiên lại kinh sợ ý tưởng ấy. Các nhà khoa học bèn nghĩ ra cách hoà giải: khoảng không của không gian chứa đầy nguyên tố thứ năm, khí aether, một chất không có các đặc tính hiện bày , nhưng chắc chắn không phải không có. But as the quantum and cosmological revolutions of the 20th century arrived, scientists never found this aether and continued to turn up empty handed. Nhưng đến thế kỷ 20 khi có cuộc cách mạng về lượng tử và vũ trụ học, các khoa học gia vẫn không hề tìm thấy chất aether, và việc tiếp tục tìm kiếm nó cũng chẳng đi đến đâu. The more we looked, through increasingly powerful telescopes and microscopes, the more we discovered nothing. In the 1920s astronomer Edwin Hubble discovered that the Andromeda nebula was actually the Andromeda galaxy, an island home of billions of stars sitting a staggering 2.5 million light-years away. As far as we could tell, all those lonely light-years were filled with not much at all, just the occasional lost hydrogen atom or wandering photon. Compared to the relatively small size of galaxies themselves (our own Milky Way stretches across for a mere 100,000 light-years), the universe seemed dominated by absence. Càng quan sát tìm kiếm qua các viễn vọng kính và kính hiển vi ngày một tối tân, tinh xảo, chúng ta càng không tìm thấy gì cả. Vào thập niên 1920 nhà thiên văn Edwin Hubble khám phá ra rằng vòm sao Andromeda thực ra là thiên hà Andromeda, một vùng biệt lập (như hòn đảo) gồm hàng tỷ vì sao cách xa trái đất 2 triệu rưỡi năm ánh sáng. Có thể nói giữa khoảng đơn độc của ngần ấy năm ánh sáng gần như không có gì cả, họa chăng thỉnh thoảng có một nguyên tử hydrogen đi lạc lối hay một proton lang thang bất định. Nếu so sánh với kích thước tương đối nhỏ của các thiên hà (dải Ngân hà của chúng ta chỉ trải dài 100.000 năm ánh sáng), thì vũ trụ dường như chỉ có sự vắng mặt ngự trị mà thôi. At subatomic scales, scientists were also discovering atoms to be surprisingly empty places. If you were to rescale a hydrogen atom so that its nucleus was the size of a basketball, the nearest electron would sit around two miles away. With not so much as a lonely subatomic tumbleweed in between. Ở cấp độ nhỏ hơn nguyên tử, các nhà khoa học cũng khám phá thấy chúng trống không một cách đáng ngạc nhiên. Nếu bạn thay đổi kích thước nguyên tử hydrogen để nhân của nó to bằng quả bóng chuyền, thì âm điện tử gần nhất sẽ nằm cách xa hạt nhân khoảng 2 dặm. Khoảng giữa chẳng có gì khác hơn là một vùng vi tế (nhỏ hơn cả nguyên tử) trống không cô quạnh. WILD HORSES COULDN’T DRAG THEM APART: Inventor Otto von Guericke’s original vacuum pump and copper hemispheres are on display in the Deutsches Museum in Munich, Germany. When von Guericke sealed the hemispheres in a vacuum, they couldn’t be separated by teams of horses. Image by Wikimedia Commons. Các chú ngựa hoang không thể kéo tách rời hai bán cầu: Ống bơm hút không khí và hai bán cầu của nhà phát minh Otto von Guericke hiện được trưng bày tại Viện Bảo tàng Đức, thành phố Munich, Đức quốc. Khi von Guericke hàn kín hai bán cầu chứa vùng chơn không, bầy ngựa không thể tách rời hai bán cầu ra được. Nothing. Absolutely nothing. Continued experiments and observations only served to confirm that at scales both large and small, we appeared to live in an empty world. Không có gì. Hoàn toàn không có gì cả. Các thí nghiệm và quan sát được tiếp tục thực hiện nhưng chỉ khẳng định rằng ở cả cấp độ lớn (vĩ mô) lẫn nhỏ (vi mô), chúng ta dường như sống trong một thế giới trống không. And then that nothingness cracked open. Within the emptiness that dominates the volume of an atom and the volume of the universe, physicists found something. Far from the sedate aether of yore, this something is strong enough to be tearing our universe apart. The void, it turns out, is alive. Và rồi cái không ấy lại vỡ tung ra. Bên trong cái không vốn ngự trị cả thể tích hạt nguyên tử và cả thể tích vũ trụ, các nhà vật lý lại tìm ra có một cái gì đó. Khác hẳn chất aether tẻ nhạt người xưa nghĩ ra, cái gì ấy lại mạnh mẽ đủ để xé toang vũ trụ. Hóa ra chơn không quả là sống động. In December 2022, an international team of astronomers released the results of their latest survey of galaxies, and their work has confirmed that the vacuum of spacetime is wreaking havoc across the cosmos. They found that matter makes up only a minority contribution to the energy budget of the universe. Instead, most of the energy within the cosmos is contained in the vacuum, and that energy is dominating the future evolution of the universe. Tháng 12 năm 2022 một nhóm các nhà thiên văn học quốc tế công bố kết quả thăm dò các thiên hà mới đây nhất của họ, và công trình này khẳng định rằng chơn không bốn chiều hiện đang hoành hành khắp vũ trụ. Họ khám phá thấy vật chất chỉ góp một phần nhỏ vào quỹ năng lượng của vũ trụ. Thay vào đó, phần lớn năng lượng trong vũ trụ nằm trong chơn không, và chính năng lượng ấy điều động sự tiến hóa của vũ trụ trong tương lai. [In physics, spacetime is a mathematical model that combines the three dimensions of space and one dimension of time into a single four-dimensional manifold. Spacetime diagrams can be used to visualize relativistic effects, such as why different observers perceive differently where and when events occur. Until the 20th century, it was assumed that the three-dimensional geometry of the universe (its spatial expression in terms of coordinates, distances, and directions) was independent of one-dimensional time. The physicist Albert Einstein helped develop the idea of spacetime as part of his theory of relativity. Trong vật lý, không-thời gian bốn chiều/spacetime là một mô hình toán học kết hợp ba chiều không gian và một chiều thời gian thành một điểm tập hợp/collection duy nhất gồm có bốn chiều. Các mô hình spacetimecó thể được dùng để hình dung các hiệu ứng tương đối, chẳng hạn việc những người quan sát khác nhau nhận thức khác nhau về nơi chốn và khi nào các sự kiện xảy ra. Mãi đến thế kỷ 20 người ta vẫn còn giả định rằng vũ trụ theo kiểu hình học ba chiều (diễn tả bằng tọa độ, khoảng cách và phương hướng) độc lập với thời gian một chiều. Nhà vật lý Albert Einstein giúp phát triển ý tưởng về điểm không-thời gian bốn chiều/spacetime, trong thuyết tương đối của ông. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spacetime.] Their work is the latest in a string of discoveries stretching back over two decades. In the late 1990s, two independent teams of astronomers discovered that the expansion of the universe is accelerating, meaning that our universe grows larger and larger faster and faster every day. The exact present-day expansion rate is still a matter of some debate among cosmologists, but the reality is clear: Something is making the universe blow up. It appears as a repulsive gravitational force, and we’ve named it dark energy. Công trình này của các nhà thiên văn là công trình mới nhất trong chuỗi các khám phá trải dài qua hai thập niên. Cuối những năm 1990, hai nhóm nghiên cứu thiên văn học độc lập nhau đã cùng khám phá ra rằng vũ trụ đang tăng tốc giãn nở, nghĩa là vũ trụ của chúng ta đang ngày càng phình to ra với tốc độ mỗi ngày một nhanh hơn. Mức bành trướng của nó hiện giờ chính xác là bao nhiêu vẫn còn đang được các nhà vũ trụ học bàn cãi, nhưng thực tế cho ta thấy rõ: Có một cái gì đó đang làm vũ trụ nổ tung. Dường như đó là lực đẩy lùi lực hấp dẫn, và chúng ta gọi đó là năng lượng tối. [What causes a repulsive gravitational force? It is shown that reduction of the gravitational mass of the system due to emitting gravitational waves leads to a repulsive gravitational force that diminishes with time but never disappears. This repulsive force may be related to the observed expansion of the Universe. https://phys.org/news/2012-01-repulsive-gravity-alternative-dark-energy.html Người ta thấy rằng việc giảm đi khối vật chất có sức hút/lực hấp dẫn trong hệ thống do các sóng hấp dẫn được lan tỏa ra đưa đến lực hấp dẫn khiến đẩy lùi ra. Lực này giảm dần theo thời gian nhưng nó không hề biến mất. Lực đẩy lùi này có thể có liên quan đến sự bành trướng của vũ trụ mà ta quan sát thấy] The trick here is that the vacuum, first demonstrated by von Guericke all those centuries ago, is not as empty as it seems. If you were to take a box (or, following von Guericke’s example, two hemispheres), and remove everything from it, including all the particles, all the light, all the everything, you would not be left with, strictly speaking, nothing. What you’d be left with is the vacuum of spacetime itself, which we’ve learned is an entity in its own right. Điểm cắc cớ ở đây là chơn không, lần đầu tiên do von Guericke minh chứng trước đây nhiều thế kỷ, nhìn tưởng thế nhưng lại không hề trống không. Nếu bạn lấy một cái hộp (hoặc lấy hai bán cầu, theo kiểu thí dụ của von Guericke), và lấy hết mọi thứ bên trong ra, gồm tất cả các hạt, tất cả ánh sáng, mọi thứ có thể có trong ấy, thì trong chơn không ấy vẫn không phải không còn gì cho bạn. Cái bạn còn chính là vùng chơn không bốn chiều không-thời gian/spacetime, mà chúng ta biết nó là một thực thể có thực.

Nothing contains all things. It is more precious than gold. Cái không chứa đựng tất cả. Nó còn quý hơn vàng.We live in a quantum universe; a universe where you can never be quite sure about anything. At the tiniest of scales, subatomic particles fizz and pop into existence, briefly experiencing the world of the living before returning back from where they came, disappearing from reality before they have a chance to meaningfully interact with anything else. Chúng ta đang sống trong một vũ trụ lượng tử — ở đấy bạn không bao giờ có thể khẳng định chắc chắn về một điều gì. Ở mức độ siêu vi tế, các hạt nhỏ hơn cả nguyên tử sủi bọt và xuất hiện, trải nghiệm trong một sát na ngắn ngủi thế giới của sự sống trước khi quay trở lại chỗ chúng xuất phát, rồi biến mất khỏi thực tại trước khi chúng có dịp tương tác với bất cứ cái gì khác một cách đáng kể. This phenomenon has various names: the quantum foam, the spacetime foam, vacuum fluctuations. This foam represents a fundamental energy to the vacuum of spacetime itself, a bare ground level on which all other physical interactions take place. In the language of quantum field theory, the offspring of the marriage of quantum mechanics and special relativity, quantum fields representing every kind of particle soak the vacuum of spacetime like crusty bread dipped in oil and vinegar. Those fields can’t help but vibrate at a fundamental, quantum level. In this view, the vacuum is singing to us, a harmony underlying reality itself. Hiện tượng này có nhiều tên gọi: bọt lương tử, bọt không-thời gian, dao động chơn không. Bọt này đại diện cho một thứ năng lượng căn bản trong khoảng chơn không bốn chiều không-thời gian, một cấp độ nền tảng gốc cho mọi tương tác vật lý khác xảy ra. Nói theo ngôn ngữ lý thuyết về trường lượng tử, là con đẻ từ cuộc phối ngẫu giữa cơ học lượng tử và thuyết tương đối đặc biệt, các trường lượng tử là chỗ biểu hiện của mọi loại hạt và chúng hút chơn không bốn chiều giống như miếng bánh mì nhúng vào dầu giấm. Các trường này không thể không rung động ở cấp độ lượng tử căn bản. Nhìn theo cách này thì chơn không đang hát cho chúng ta nghe, một cung điệu hài hòa tiềm tàng chính nơi thực tại. Quantum fields are the quantum theoretical generalizations of classical fields. The two archetypal classical fields are Maxwell’s electromagnetic field and Einstein’s metric field of gravitation Các trường lượng tử là các trường cổ điển được khái quát hoá theo lý thuyết lượng tử. Hai trường cổ điển tiêu biểu là trường điện từ Maxwell và trường lực hấp dẫn Einstein.] In our most advanced quantum theories, we can calculate the energy contained in the vacuum, and it’s infinite. As in, suffusing every cubic centimeter of space and time is an infinite amount of energy, the combined efforts of all those countless but effervescent particles. This isn’t necessarily a problem for the physics that we’re used to, because all the interactions of everyday experience sit “on top of” (for lack of a better term) that infinite tower of energy—it just makes the math a real pain to work with. Theo các lý thuyết lượng tử cao cấp nhất, chúng ta có thể tính được năng lượng chứa trong vùng chơn không, và năng lượng này vô tận. Giống như, khi một lượng năng lượng vô tận lan tràn khắp từng centimet khối trong khoảng không gian và thời gian, đó là những khả năng hợp lại của tất cả số các hạt vô định đang sôi bọt. Đây không nhất thiết là vấn đề đặt ra cho ngành vật lý mà chúng ta vốn quen thuộc, vì mọi tương tác được trải nghiệm hàng ngày đều xảy ra trên “đỉnh” (không thể có từ ngữ nào hay hơn) tháp năng lượng vô tận này – chỉ có điều phép giải về bài toán này là cực kỳ khó. All this would be mathematically annoying but otherwise unremarkable except for the fact that in Einstein’s general theory of relativity, vacuum energy has the curious ability to generate a repulsive gravitational force. We typically never notice such effects because the vacuum energy is swamped by all the normal mass within it (in von Guericke’s case, the atmospheric pressure surrounding his hemispheres was the dominant force at play). But at the largest scales there’s so much raw nothingness to the universe that these effects become manifest as an accelerated expansion. Recent research suggests that around 5 billion years ago, the matter in the universe diluted to the point that dark energy could come to the fore. Today, it represents roughly 70 percent of the entire energy budget of the cosmos. Studies have shown that dark energy is presently in the act of ripping apart the large-scale structure of the universe, tearing apart superclusters of galaxies and disentangling the cosmic web before our eyes. Tất cả điều này có thể khiến ta khó chịu về mặt toán học (khi phải lý giải bằng toán) nhưng, mặt khác, nó lại chẳng có gì độc đáo ngoại trừ sự kiện là, theo thuyết tương đối tổng quát của Einstein, năng lượng chơn không lại có khả năng kỳ lạ là nó phát ra một lực hấp dẫn khiến đẩy lùi ra. Thường chúng ta không bao giờ ghi nhận những hiệu ứng như thế vì năng lượng chơn không ngập đầy tất cả khối vật chất bình thường nằm bên trong nó (trong trường hợp von Guericke, áp suất không khí chung quanh hai bán cầu là lực chủ đạo đang hiện hành). Nhưng ở các cấp độ lớn nhất, cái không nguyên tuyền có mặt khắp cả vũ trụ nhiều đến nỗi những hiệu ứng này trở thành biểu hiện theo kiểu bành trướng gia tốc. Nghiên cứu mới đây cho thấy cách đây khoảng 5 tỷ năm, vật chất trong vũ trụ loãng yếu đến độ năng lượng tối có thể hiển lộ. Ngày nay năng lượng tối chiếm khoảng 70% toàn bộ quỹ năng lượng của vũ trụ. Các nghiên cứu cho thấy năng lượng tối hiện giờ đang mặc sức tung hoành phá vỡ cấu trúc vĩ mô của vũ trụ, xé bung các chùm thiên hà to lớn và tháo tung mạng vũ trụ trước mắt của chúng ta. [Supercluster, a group of galaxy clusters typically consisting of 3 to 10 clusters and spanning as many as 200,000,000 light-years. They are the largest structures in the universe. Siêu chùm là một nhóm thiên hà, thường gồm từ 3 đến 10 chùm, trải ra có thể nhiều đến 200,000,000 năm ánh sáng. Chúng là những cấu trúc lớn nhất trong vũ trụ.] But the acceleration isn’t all that rapid. When we calculate how much vacuum energy is needed to create the dark energy effect, we only get a small number. Nhưng mức tăng tốc cũng không phải chỉ có quá nhanh. Khi chúng ta tính toán cần bao nhiêu năng lượng chơn không để tạo ra hiệu ứng năng lượng tối, chúng ta chỉ đạt được một con số nhỏ. But our quantum understanding of vacuum energy says it should be infinite, or at least incredibly large. Definitely not small. This discrepancy between the theoretical energy of the vacuum and the observed value is one of the greatest mysteries in modern physics. And it leads to the question about what else might be lurking in the vast nothingness of our atoms and our universe. Perhaps von Guericke was right all along. “Nothing contains all things,” he wrote. “It is more precious than gold, without beginning and end, more joyous than the perception of bountiful light, more noble than the blood of kings, comparable to the heavens, higher than the stars, more powerful than a stroke of lightening, perfect and blessed in every way.” Nhưng với sự hiểu biết lượng tử về năng lượng chơn không của chúng ta thì năng lượng ấy vô tận, hoặc, chí ít, nó cực kỳ lớn. Chắc chắn nó không hề nhỏ. Sự sai biệt này giữa năng lượng chơn không theo lý thuyết và trị số của nó theo quan sát là một trong những điều bí ẩn nhất của vật lý hiện đại. Và nó dẫn đến câu hỏi về còn có cái gì khác có thể đang ẩn khuất trong cái không to lớn nằm trong các hạt nguyên tử và trong vũ trụ của chúng ta. Có lẽ ngay từ đầu von Guericke đã nói đúng. Ông viết: “Cái không hàm chứa tất cả. Nó còn quý hơn vàng, không có bắt đầu hay kết thúc, rộn ràng hơn cả ánh sáng ngập tràn mà chúng ta nhận thức được, nó thượng đẳng hơn dòng dõi vua chúa, có thể ví nó như trời, nó cao hơn các vì sao, mạnh mẽ hơn cả sét trời đánh, nó toàn hảo đủ đầy phước báu muôn mặt.” Nguồn: https://nautil.us/the-remarkable-emptiness-of-existence-256323/?utm_source=pocket-newtab *Paul M. Sutter is a research professor in astrophysics at the Institute for Advanced Computational Science at Stony Brook University and a guest researcher at the Flatiron Institute in New York City. He is the author of Your Place in the Universe: Understanding Our Big, Messy Existence. Paul M. Sutter là giáo sư nghiên cứu về ngành vật lý thiên văn tại Viện Khoa Học Vi Tính Cao Cấp của Đại học Stony Brook và ông cũng tham gia nghiên cứu tại Viện Flatiron ở thành phố New York. Ông là tác giả quyển Chỗ Của Bạn Trong Vũ Trụ: Tìm Hiểu Sự Hiện Hữu To Lớn, Hỗn Độn Của Chúng Ta. [A guest researcher is a scientist, engineer, and/or student who are permitted to engage in scientific studies and investigations. Khách mời nghiên cứu là một nhà khoa học, một kỹ sư, hoặc là một sinh viên được cho phép tham gia vào các công trình tìm tòi nghiên cứu.] Các liên kết khác để tham khảo: Bản tiếng Anh: https://nautil.us/the-remarkable-emptiness-of-existence-256323/?utm_source=pocket-newtab The Remarkable Emptiness of Existence Early scientists didn’t know it, but we do now: The void in the universe is alive. By Paul M. Sutter January 4, 2023 In 1654 a German scientist and politician named Otto von Guericke was supposed to be busy being the mayor of Magdeburg. But instead he was putting on a demonstration for lords of the Holy Roman Empire. With his newfangled invention, a vacuum pump, he sucked the air out of a copper sphere constructed of two hemispheres. He then had two teams of horses, 15 in each, attempt to pull the hemispheres apart. To the astonishment of the royal onlookers, the horses couldn’t separate the hemispheres because of the overwhelming pressure of the atmosphere around them. Von Guericke became obsessed by the idea of a vacuum after learning about the recent and radical idea of a heliocentric universe: a cosmos with the sun at the center and the planets whipping around it. But for this idea to work, the space between the planets had to be filled with nothing. Otherwise friction would slow the planets down. The vacuum is singing to us, a harmony underlying reality itself. Scientists, philosophers, and theologians across the globe had debated the existence of the vacuum for millennia, and here was von Guericke and a bunch of horses showing that it was real. But the idea of the vacuum remained uncomfortable, and only begrudgingly acknowledged. We might be able to artificially create a vacuum with enough cleverness here on Earth, but nature abhorred the idea. Scientists produced a compromise: The space of space was filled with a fifth element, an aether, a substance that did not have much in the way of manifest properties, but it most definitely wasn’t nothing. But as the quantum and cosmological revolutions of the 20th century arrived, scientists never found this aether and continued to turn up empty handed. The more we looked, through increasingly powerful telescopes and microscopes, the more we discovered nothing. In the 1920s astronomer Edwin Hubble discovered that the Andromeda nebula was actually the Andromeda galaxy, an island home of billions of stars sitting a staggering 2.5 million light-years away. As far as we could tell, all those lonely light-years were filled with not much at all, just the occasional lost hydrogen atom or wandering photon. Compared to the relatively small size of galaxies themselves (our own Milky Way stretches across for a mere 100,000 light-years), the universe seemed dominated by absence. At subatomic scales, scientists were also discovering atoms to be surprisingly empty places. If you were to rescale a hydrogen atom so that its nucleus was the size of a basketball, the nearest electron would sit around two miles away. With not so much as a lonely subatomic tumbleweed in between. WILD HORSES COULDN’T DRAG THEM APART: Inventor Otto von Guericke’s original vacuum pump and copper hemispheres are on display in the Deutsches Museum in Munich, Germany. When von Guericke sealed the hemispheres in a vacuum, they couldn’t be separated by teams of horses. Image by Wikimedia Commons. https://assets.nautil.us/sites/3/nautilus/7qPwefwg-Sutter_BREAKER.png?auto=compress&fit=scale&fm=png&h=1359&ixlib=php-3.3.1&w=1536&wpsize=1536x1536 Nothing. Absolutely nothing. Continued experiments and observations only served to confirm that at scales both large and small, we appeared to live in an empty world. And then that nothingness cracked open. Within the emptiness that dominates the volume of an atom and the volume of the universe, physicists found something. Far from the sedate aether of yore, this something is strong enough to be tearing our universe apart. The void, it turns out, is alive. In December 2022, an international team of astronomers released the results of their latest survey of galaxies, and their work has confirmed that the vacuum of spacetime is wreaking havoc across the cosmos. They found that matter makes up only a minority contribution to the energy budget of the universe. Instead, most of the energy within the cosmos is contained in the vacuum, and that energy is dominating the future evolution of the universe. Their work is the latest in a string of discoveries stretching back over two decades. In the late 1990s, two independent teams of astronomers discovered that the expansion of the universe is accelerating, meaning that our universe grows larger and larger faster and faster every day. The exact present-day expansion rate is still a matter of some debate among cosmologists, but the reality is clear: Something is making the universe blow up. It appears as a repulsive gravitational force, and we’ve named it dark energy. The trick here is that the vacuum, first demonstrated by von Guericke all those centuries ago, is not as empty as it seems. If you were to take a box (or, following von Guericke’s example, two hemispheres), and remove everything from it, including all the particles, all the light, all the everything, you would not be left with, strictly speaking, nothing. What you’d be left with is the vacuum of spacetime itself, which we’ve learned is an entity in its own right. Nothing contains all things. It is more precious than gold. We live in a quantum universe; a universe where you can never be quite sure about anything. At the tiniest of scales, subatomic particles fizz and pop into existence, briefly experiencing the world of the living before returning back from where they came, disappearing from reality before they have a chance to meaningfully interact with anything else. This phenomenon has various names: the quantum foam, the spacetime foam, vacuum fluctuations. This foam represents a fundamental energy to the vacuum of spacetime itself, a bare ground level on which all other physical interactions take place. In the language of quantum field theory, the offspring of the marriage of quantum mechanics and special relativity, quantum fields representing every kind of particle soak the vacuum of spacetime like crusty bread dipped in oil and vinegar. Those fields can’t help but vibrate at a fundamental, quantum level. In this view, the vacuum is singing to us, a harmony underlying reality itself. In our most advanced quantum theories, we can calculate the energy contained in the vacuum, and it’s infinite. As in, suffusing every cubic centimeter of space and time is an infinite amount of energy, the combined efforts of all those countless but effervescent particles. This isn’t necessarily a problem for the physics that we’re used to, because all the interactions of everyday experience sit “on top of” (for lack of a better term) that infinite tower of energy—it just makes the math a real pain to work with. All this would be mathematically annoying but otherwise unremarkable except for the fact that in Einstein’s general theory of relativity, vacuum energy has the curious ability to generate a repulsive gravitational force. We typically never notice such effects because the vacuum energy is swamped by all the normal mass within it (in von Guericke’s case, the atmospheric pressure surrounding his hemispheres was the dominant force at play). But at the largest scales there’s so much raw nothingness to the universe that these effects become manifest as an accelerated expansion. Recent research suggests that around 5 billion years ago, the matter in the universe diluted to the point that dark energy could come to the fore. Today, it represents roughly 70 percent of the entire energy budget of the cosmos. Studies have shown that dark energy is presently in the act of ripping apart the large-scale structure of the universe, tearing apart superclusters of galaxies and disentangling the cosmic web before our eyes. But the acceleration isn’t all that rapid. When we calculate how much vacuum energy is needed to create the dark energy effect, we only get a small number. But our quantum understanding of vacuum energy says it should be infinite, or at least incredibly large. Definitely not small. This discrepancy between the theoretical energy of the vacuum and the observed value is one of the greatest mysteries in modern physics. And it leads to the question about what else might be lurking in the vast nothingness of our atoms and our universe. Perhaps von Guericke was right all along. “Nothing contains all things,” he wrote. “It is more precious than gold, without beginning and end, more joyous than the perception of bountiful light, more noble than the blood of kings, comparable to the heavens, higher than the stars, more powerful than a stroke of lightening, perfect and blessed in every way.” Paul M. Sutter is a research professor in astrophysics at the Institute for Advanced Computational Science at Stony Brook University and a guest researcher at the Flatiron Institute in New York City. He is the author of Your Place in the Universe: Understanding our Big, Messy Existence.

Ta Thấy Hình Ta Những Miếu Đền

Nhà thơ Mai Thảo

Jan 10, 2023

Mai Thảo tên thật là Nguyễn Ðăng Quý, bút hiệu khác Nguyễn Ðăng, ông sinh ngày 8 Tháng Sáu, 1927, tại chợ Cồn, xã Quần Phương Hạ, huyện Hải Hậu, tỉnh Nam Ðịnh.

Mai Thảo thích thơ, thuộc thơ, viết nhiều bài thơ dài từ năm 16, 17 tuổi, làm cả kịch thơ. Những tập thơ đầu đã thất lạc.

Nhà văn Mai Thảo. (Hình: Cao Lĩnh)

Khi vào Nam viết văn, làm báo, ông bỏ thơ. Mười năm trước khi mất, Mai Thảo cho xuất bản tập thơ duy nhất “Ta Thấy Hình Ta Những Miếu Đền,” cô đọng những cô đơn mất mát của một đời người. (Thụy Khuê)

ta thấy hình ta những miếu đền

ta thấy tên ta những bảng đường

đời ta, sử chép cả ngàn chương

sao không, hạt cát sông Hằng ấy

còn chứa trong lòng cả đại dương

ta thấy hình ta những miếu đền

tượng thờ nghìn bệ những công viên

sao không, khói với hương sùng kính

đều ngát thơm từ huyệt lãng quên

ta thấy muôn sao đứng kín trời

chờ ta, Bắc Đẩu trở về ngôi

sao không, một điểm lân tinh vẫn

cháy được lên từ đáy thẳm khơi

ta thấy đường ta Chúa hiện hình

vườn ta Phật ngủ, ngõ thần linh

sao không, tâm thức riêng bờ cõi

địa ngục ngươi là, kẻ khác ơi!

ta thấy nơi ta trục đất ngừng

và cùng một lúc trục đời ngưng

sao không, hạt bụi trong lòng trục

cũng đủ vòng quay phải đứng dừng

ta thấy ta đêm giữa sáng ngày

ta ngày giữa tối thẳm đêm dài

sao không, nhật nguyệt đều tăm tối

tự thuở chim hồng rét mướt bay

ta thấy nhân gian bỗng khóc òa

nhìn hình ta khuất bóng ta xa

sao không, huyết lệ trong trời đất

là phát sinh từ huyết lệ ta

ta thấy rèm nhung khép lại rồi

hạ màn, thế kỷ hết trò chơi

sao không, quay gót, tên hề đã

chán một trò điên diễn với người

ta thấy ta treo cổ dưới cành

rất hiền giấc ngủ giữa rừng xanh

sao không, sao chẳng không là vậy

khi chẳng còn chi ở khúc quanh.

New nation, new ideas: A study finds immigrants out-innovate native-born Americans

https://www.npr.org/sections/money/2023/01/10/1147391639/new-nation-new-ideas-a-study-finds-immigrants-out-innovate-native-born-americans

New nation, new ideas: A study finds immigrants out-innovate native-born Americans

January 10, 20236:31 AM ET

Greg Rosalsky

Sergey Brin, co-founder Google; Satya Nadella, head of Microsoft; Hedy Lamarr, a Hollywood actress who, quite incredibly, was also a pioneering inventor behind Wi-Fi and bluetooth; Elon Musk; Chien-Shiung Wu, who helped America build the first atom bomb; Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone; James Naismith, the inventor of basketball; Nikola Tesla, one of the most important minds behind the creation of electricity and radio.

What do all these innovators have in common? They were all immigrants to the United States.

Many studies over the years have suggested that immigrants are vital to our nation's technological and economic progress. Today, around a quarter of all workers in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields are immigrants.

But while there's plenty of evidence suggesting that immigrants play an important role in American innovation, a group of economists — Shai Bernstein, Rebecca Diamond, Abhisit Jiranaphawiboon, Timothy McQuade, and Beatriz Pousada — wanted to find a more precise estimate of how much immigrants contribute.

In a fascinating new working paper, the economists link patent records to more than 230 million Social Security numbers. With this incredible dataset, they are able to suss out who among patent-holders are immigrants (by cross-referencing their year of birth and the year they were assigned their Social Security number).

The economists find that, between 1990 and 2016, 16 percent of all US inventors were immigrants. More than that, they find that the "average immigrant is substantially more productive than the average US-born inventor." Immigrant inventors produced almost a quarter of all patents during this period. These patents were disproportionately likely to be cited (a sign that they were valuable to their fields) and seem to have more financial value than the typical native-born patent. The economists also find evidence suggesting that immigrant inventors help native-born inventors become more productive. All in all, the economists estimate that immigrants are responsible for roughly 36% of innovation in America.

As for why immigrant inventors tend to be so productive and innovative, the economists entertain various explanations. Immigrant innovators may be motivated to come — and are able to come — to the United States because there's something special about their character, intelligence, or motivation. Or maybe it's because they live, work, and think differently when they come here. The economists find these immigrants tend to move to the most productive areas of the country. They tend to have a greater number of collaborators when they work here. And, as the economists write, they also "appear to facilitate the importation of foreign knowledge into the United States, with immigrant inventors relying more heavily on foreign technologies and collaborating more with foreign inventors."

Immigrants, they suggest, help create a melting pot of knowledge and ideas, which has clear benefits when it comes to innovation.

It's Hard Being An Immigrant These Days

Many immigrants working in innovation sectors are here on H1-B visas, which allow around 85,000 people to come to the United States each year, and create a potential pathway for them to become legal permanent residents. These visas tether immigrants to a particular job. But, as our NPR colleague Stacey Vanek Smith reported last month, "if they lose that job, a countdown clock starts." They have 60 days to find a new job or they must exit the country.

With financial turmoil roiling the tech sector, companies have been laying off tons of workers. As Stacey reported, there are now thousands of unemployed H1-B visa holders frantically trying to find new jobs so they can stay in the country. But ongoing layoffs and hiring freezes are making that particularly difficult.

In a recent editorial, the editors of Bloomberg argue that the current struggle of immigrants in tech "underscores how a flawed system is jeopardizing America's ability to attract and retain the foreign-born talent it needs." This system, they argue, is "not only cruel but self-defeating... rather than expanding the pipeline for skilled foreign workers, the US's onerous policies are increasingly pushing them away, with pro-immigration countries like Canada and Australia becoming more attractive destinations for global talent."

With the United States taking an increasingly nativist turn in recent years, it's become more common to hear anti-immigrant rhetoric, about them taking jobs, committing crimes, and "replacing" us. The economists' new study serves as another potent reminder that immigrants have tremendous value for our economy. Not just as a cheap labor force, but as a group of innovators who help us build new businesses, create jobs, make our companies more productive, and produce products and ideas that enrich our lives and improve our standard of living. Call it the Great Enhancement Theory.

Sunday, January 8, 2023

Nhân chứng người Việt kể về Cách mạng Nhung 1989 tại Tiệp Khắc

https://www.bbc.com/vietnamese/articles/c2ev9yry81go

Nhân chứng người Việt kể về Cách mạng Nhung 1989 tại Tiệp Khắc

Nhà báo Nguyễn Giang (bìa phải) nói chuyện với các nhân chứng của một thời kỳ lịch sử ở Tiệp Khắc

6 tháng 1 2023

Vào ngày 17/11/1989, hàng ngàn sinh viên tụ tập tại thủ đô Prague của Tiệp Khắc, biểu tình ôn hoà để kỷ niệm Ngày Sinh viên Quốc tế.

Không mấy ai ngờ đến rằng cuộc biểu tình có vẻ như vô hại hôm đó đã châm ngòi cho việc sụp đổ nhanh chóng chỉ 10 ngày sau đó của chính quyền nước Tiệp Khắc XHCN vốn đã nắm quyền hơn 40 năm tại quốc gia Trung Âu.

Cuộc biểu tình ôn hoà của sinh viên kết thúc trong bạo lực tại trung tâm Prague, với việc cảnh sát chống bạo động chặn kín các lối thoát và đánh đập tàn nhẫn những người tham gia, từ đó dẫn tới cuộc Cách mạng Nhung, một làn sóng biểu tình mạnh mẽ diễn ra gần như hàng ngày tại các thành phố trên toàn quốc.

Các nhân chứng người Việt kể lại với BBC News Tiếng Việt vào đầu tháng 12/2022 về những gì họ tận mắt chứng kiến những gì diễn ra trong Cách mạng Nhung và quá trình chuyển đổi của Cộng hoà Czech trong hơn ba thập niên qua

Họ chia sẻ cái nhìn cá nhân về ảnh hưởng của quá trình này đối với đời sống chính trị, xã hội Việt Nam cũng như đối với cộng đồng người Việt sinh sống tại Czech kể từ đó tới nay.

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/800/cpsprodpb/18db/live/dec06810-8cee-11ed-a9e7-a9514884ef58.png

Ông Phạm Hữu Uyển nhớ lại về giai đoạn biến động cuối 1989 ở Prague

"Hồi đang học năm thứ tư Đại học Tổng hợp Prague thì tôi đi thực tập tại Viện Máy Toán học, công ty duy nhất ở Tiệp khi đó sản xuất máy tính, cả phần cứng và phần mềm," ông Phạm Hữu Uyển nhớ lại.

"Sang Tiệp học tập được một thời gian, tôi nhận thấy người dân ở đây không ưa chế độ Cộng sản. Các bạn sinh viên học cùng thì chửi Cộng sản liên mồm. Từ Việt Nam, một nước Cộng sản sang, tôi thấy giật mình vì thấy họ 'đi xa' hơn mình rất nhiều."

"Làm việc tại Viện một thời gian, tôi chơi thân với vài người bạn Tiệp. Từ thời 1984, 1985, trong môi trường đó, tôi được đọc những tài liệu mà họ in ấn tại công ty."

"Đến đầu năm 1989, bắt đầu có vài cuộc biểu tình nổ ra rất mạnh rồi."

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/800/cpsprodpb/8adc/live/06bdae40-8cef-11ed-a491-ef14dc92a205.png

Cựu sinh viên Chu Đình Lân là người trực tiếp tham dự cuộc tuần hành lịch sử 17/11/1989 ở thủ đô Liên bang CHXHCN Tiệp Khắc

Ông Chu Đình Lân, người trực tiếp tham dự cuộc tuần hành lịch sử 17/11, nhớ lại:

"Hôm đó là chiều thứ Sáu. Đó là cuộc biểu tình đã được nhà nước chính thức cho phép tổ chức. Họ tổ chức tại phố Albertov, ở chỗ khoa Tự nhiên và khoa Y, nơi tôi học năm thứ ba.

"Sau đó đoàn người đi tới Vysehrad, tức là khu mộ danh nhân, nằm cách đó khoảng 1km rồi đi dọc bờ sông để rẽ vào Quảng trường Wenceslas.

"Lúc đó thì cảnh sát chặn lại, đàn áp ở phố Narodni, khiến rất nhiều người bị thương.

"Có tin là một sinh viên chết, gây thêm mức độ phẫn nộ của giới sinh viên và dân chúng. Tin này như ngòi nổ, tạo mức độ hăng hái cho mọi người tiếp tục biểu tình.

"Sang đến thứ Bảy, Chủ Nhật, sinh viên tiếp tục tổ chức các hoạt động ngấm ngầm ở trong ký túc xá. Diễn đàn Công dân của Tiệp cũng được thành lập vào những ngày này.

"Giới trí thức, văn nghệ sĩ tập hợp bên nhau, và Diễn đàn Công dân được chính thức thành lập vào ngày 19/11, trong đó có ông Havel và các nhà bất đồng chính kiến khác."

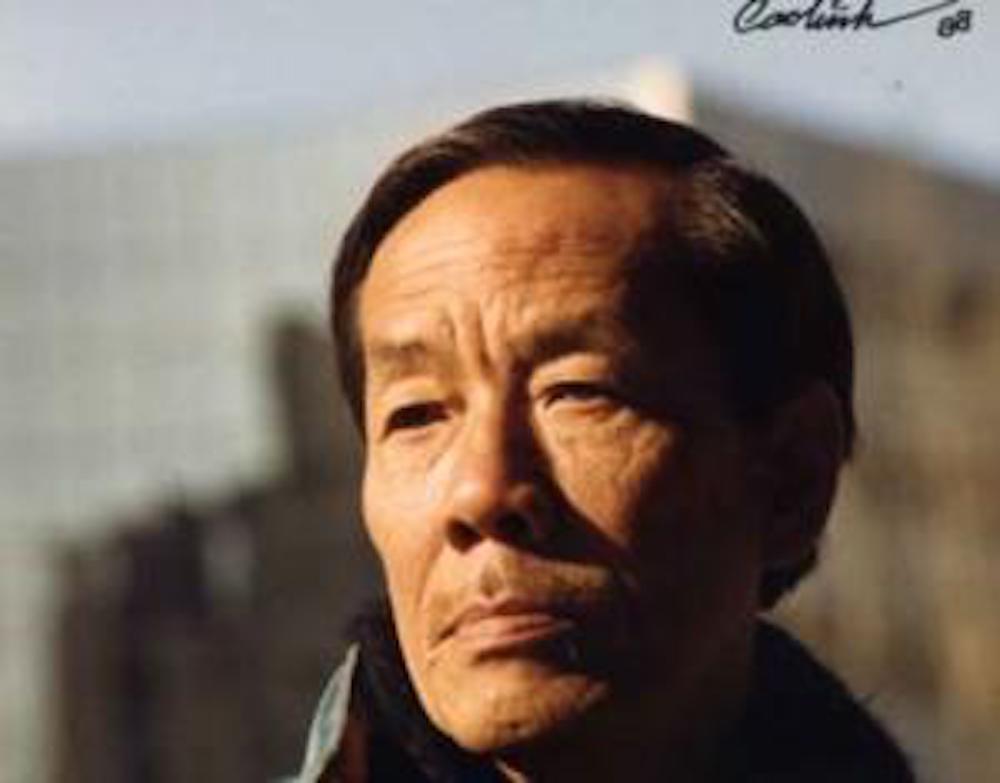

Cây viết Vaclav Havel năm 1989 nổi lên thành gương mặt hàng đầu trong giới bất đồng chính kiến Tiệp Khắc trong cuộc Cách mạng Nhung, và trở thành tổng thống đầu tiên của Tiệp thời hậu Cộng sản.

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/800/cpsprodpb/faac/live/51bb1180-8cef-11ed-888e-5f7a68a59acb.jpg

Nhân dân Czech xuống đường đòi tự do

Không lâu sau đó, ngày 31/12/2022, Tiệp Khắc chia tách thành Cộng hoà Czech và Slovakia, một trong những cuộc "chia tay" hiếm hoi không để xảy ra tổn thất nhân mạng nào.

Cuộc 'Ly hôn Nhung' đưa Cộng hoà Czech trở thành cựu quốc gia đầu tiên của Khối Đông Âu giành được vị thế nền kinh tế phát triển, và gia nhập Liên hiệp Âu châu vào năm 2004.

"Tôi sang Tiệp năm 1980. Thời gian 1989, tôi đang học tại chính phố Narodni nên chứng kiến được những buổi biểu tình của sinh viên và giới hoạt động xã hội," ông Nguyễn Cường nói. "Đó là một may mắn của cá nhân, khi tôi được chứng kiến những gì xảy ra từ trước Cách mạng Nhung cho đến tận bây giờ."

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/764/cpsprodpb/1040/live/6f4c09c0-8cef-11ed-a491-ef14dc92a205.png

Doanh nhân, nhà hoạt động Nguyễn Cường nay vẫn tiếp tục theo đuổi lý tưởng tự do, dân chủ của Cách mạng Nhung nhưng để hướng tới Việt Nam

Cách mạng Nhung tại Tiệp Khắc diễn ra trong bối cảnh có những biến động chính trị lớn lao tại Liên Xô và các nước Cộng sản khác tại Đông Âu.

Liên Xô vào giữa thập niên 1980, dưới thời lãnh đạo của ông Gorbachev, bắt đầu tiến hành các chính sách 'glasnost' - cởi mở, minh bạch hơn trong hoạt động của chính quyền, và 'perestroika' - nhằm nỗ lực hiện đại hoá và 'tái thiết' Liên bang Xô-viết.

Tại các nước cộng sản khác, một làn sóng phản đối nổ ra ở nhiều nơi.

Ba Lan có phong trào của Công đoàn Đoàn kết kêu gọi chấm dứt quyền kiểm soát của Liên Xô tại nước này từ trước.

Bức tường Berlin tại Đức bị giật đổ vào ngày 9/11/1989, càng tạo hy vọng cho người dân Tiệp Khắc trong việc đấu tranh đòi dân chủ.

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/800/cpsprodpb/3ff4/live/84a3e7c0-8cef-11ed-a491-ef14dc92a205.png

Phiên dịch viên Ngô Thuý Vân, người chuyển tới Cộng hoà Czech sống và làm việc nhiều năm sau sự kiện năm 1989 nói về cuộc sống ở một xã hội mới

Một số người cho rằng sự chuyển đổi thành công sau Cách mạng Nhung có tác động đáng kể tới đời sống chính trị ở Việt Nam và của cộng đồng người Việt tại Cộng hoà Czech.

Ngô Thuý Vân, một bạn trẻ chuyển tới Cộng hoà Czech sống và làm việc nhiều năm sau sự kiện 17/11/1989, nói:

"Nhờ Cách mạng Nhung và các thế hệ đi trước, tôi cảm giác như mình được sinh ra lần thứ hai. Lúc còn ở Việt Nam, tôi có nghe nói nhưng không đủ thông tin để ghép tất cả các mảnh ghép. Sang tới đây, tôi thấy mình được hưởng nhờ thành quả của Cách mạng Nhung trong cả công việc lẫn đời sống."

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/633/cpsprodpb/c410/live/fd8766f0-8cfc-11ed-89ec-51b7f9c98544.jpg

Ảnh các trí thức bất đồng chính kiến Tiệp Khắc: Jiri Kolar và Vaclav Havel trong quán cà phê nổi tiếng Slava ở Prague

Những tài liệu, tư tưởng của nhà bất đồng chính kiến Vaclav Havel, lãnh tụ nổi trội của Cách mạng Nhung, đã có tác động to lớn tới giới hoạt động dân sự tại Việt Nam, theo ông Nguyễn Cường, người cũng là thành viên chủ chốt của nhóm Văn Lang, một nhóm hoạt động của người Việt tại Cộng hoà Czech.

Bản thân ông Havel từng khuyến khích, ủng hộ người Việt tại Prague tham gia các hoạt động quảng bá cho tư tưởng dân chủ.

"Khi Nhóm Văn Lang tham gia dịch và hiệu đính cuốn 'Quyền lực của những kẻ không quyền lực', Nhà xuất bản Giấy vụn xuất bản, tôi nghe nói trong nước cấm quyển sách này, nhưng những người hoạt động xã hội dân sự tại Việt Nam rất quý. Họ thấy cuốn sách đó bổ sung cho niềm tin của họ," ông Nguyễn Cường nói.

"Khi đọc cuốn sách này [của ông Vaclav Havel], họ thấy có một phần của họ trong đó. Những gì xảy ra tại Tiệp Khắc tác động rất nhiều đến tình hình đấu tranh ở Việt Nam."

Ngày nay, CH Czech là một thành viên chủ chốt của EU và Nato ở Đông Âu, với mức sống cao, nền báo chí tự do.

Cuộc sống văn minh, êm đềm của xã hội Czech trong thế kỷ 21 đang tiếp tục thu hút di dân Việt Nam tới tìm cuộc sống mới.

Nhưng các vị khách tại Prague cũng chia sẻ với BBC về tác động xấu của cuộc chiến Nga gây ra ở láng giềng Ukraine, và nói về tâm tư của người Việt tại Czech về sự kiện mới nhất này.

Toàn bộ nội dung video do Nguyễn Giang, Bình Khuê và David Wilkin thực hiện từ Prague cuối năm 2022 có trên YouTube tại đây.

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/511/cpsprodpb/6773/live/42429df0-8cfd-11ed-89ec-51b7f9c98544.jpg

Nhóm thân hữu người Việt quý trọng các giá trị của Cách mạng Nhung vẫn thường gặp mặt trong quán cà phê Slava, nơi Vaclav Havel, tổng thống dân chủ đầu tiên của CH Czech, từng ngồi cùng bạn bè văn nghệ sĩ.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)